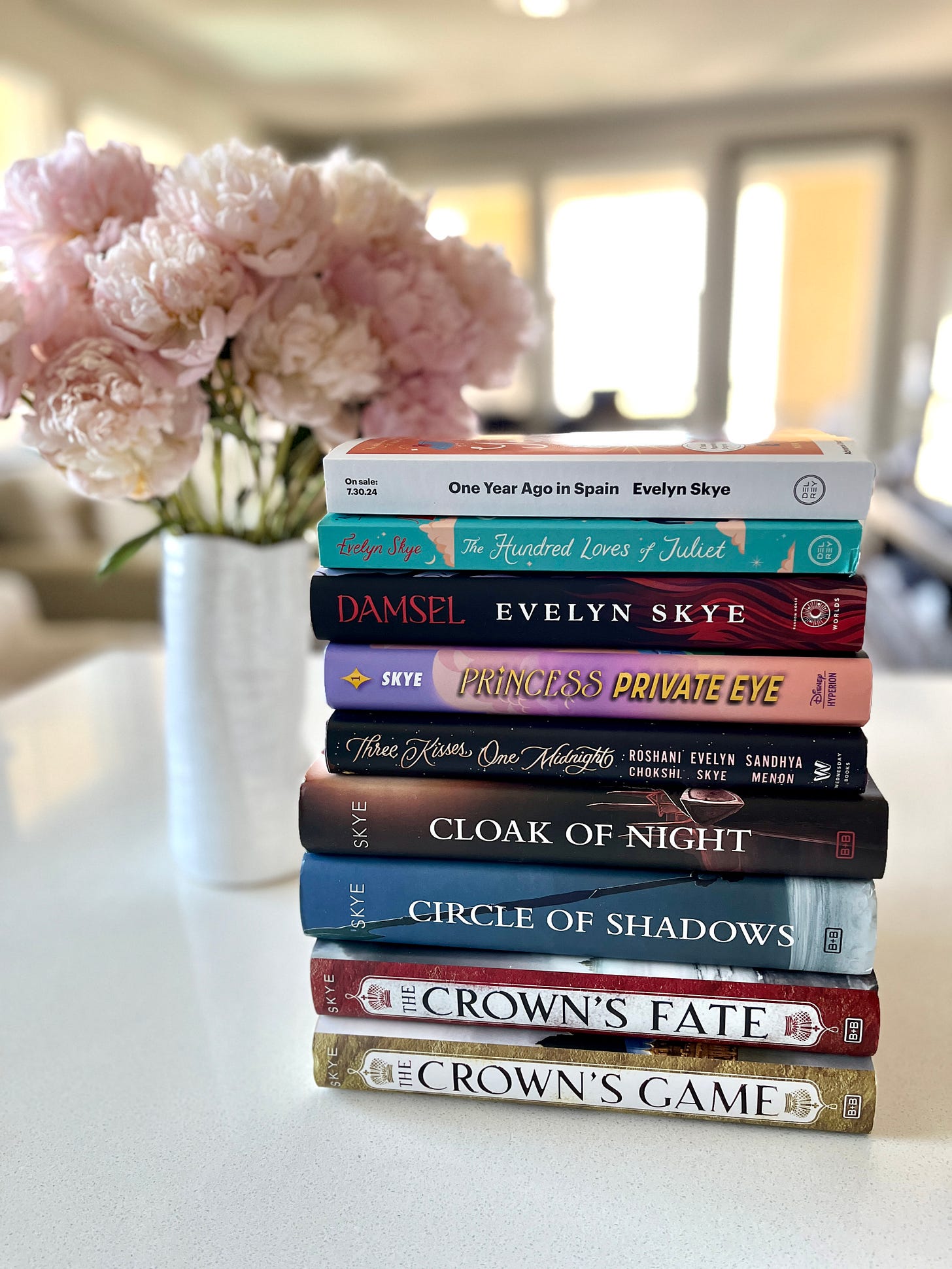

Hi, Everyone—Today I’m excited to share a really fun interview: Earlier this year I met Evelyn Skye, the California-based New York Times best-selling author of nine books, including Damsel, which is a literary and film collaboration with Netflix (the film version stars Millie Bobby Brown, Angela Bassett, and Robin Wright and debuted as the #1 movie globally on Netflix). Evelyn also has a fantastic Substack, WORDPLAY with Evelyn Skye, where she shares behind-the-scenes peeks at the novelist life along with author interviews and also hosts a book club. She and I got on Zoom a few days after we met to talk about her life-long obsession with food and how she works food into her books as a way of world building and giving insight into characters. Here’s what she told me, condensed and edited for clarity:

Evelyn Skye

I grew up in Southern California. I was actually born in Baltimore, but my parents are immigrants from Taiwan, so, they were basically in shock when winter happened, because Taiwan is a tropical island. My dad was a resident in pediatrics. At that time they were still doing day-and-a-half long shifts without any sleep, and then he was having to drive in the snow, which he had never even seen before. And my mom was at home with little baby me, terrified the entire time that her husband wasn't going to come home because he would get in some kind of car accident when he was sleepless and driving on black ice. She very soon convinced him to please try to move out to a place like California, where there is more sun. We moved when I was about one and a half.

So, basically, my entire life has been in California—other than that year and a half in Baltimore when I was a baby and then the three years I was in Boston for law school (though I came back in the summers to work in California). I grew up in Southern California, in two towns called Upland and Claremont, about 40 miles east of LA. Claremont is a college town, and it was a mostly white neighborhood. I think there were maybe just three kids, including me, in my grade that were Asian. But my parents were part of the Taiwanese American medical community there. We would have an annual Christmas party where there would be Taiwanese-Chinese banquet food.

Once every couple of weeks we would take a family trek to the Asian grocery store. Now they're everywhere, but back then they were they were far away. It was like 45 minutes or more in the car. While my parents were doing the grocery shopping for an hour, my brother and I would get to go to the cookie and candy aisle. We would spend almost the entire time there, because we would each get to buy one thing. That was like our treat. And it was such a big debate every time. I was the older sibling, so I was always very judgmental about what my brother would get, like, “You wasted your pick on those? Those are disgusting.”

My mom made a lot of kind of traditional Taiwanese or Chinese dishes, a lot of stir fry. It's very common to always have silken tofu at dinner with a kind of soy sauce drizzle on it and some bonito flakes. So, that was a cold appetizer that we'd always have that my mom would make. Her meals look kind of like a typical Chinese banquet spread, where you're shocked that she's put this out every single night. There’s the tofu dish, there's two different kinds of veggies, there's some kind of stir-fry with meat and veggies, and rice, and then always fruit for dessert—if we even have like a “dessert,” because sweet things like cakes are more for special occasions in Taiwanese culture.

But my parents were also very much into trying to make sure that we would assimilate into the American culture, which was a very white American culture where we lived. For example, every year after Thanksgiving break, kids would go back to school and the teachers would say, “What did you have for Thanksgiving?” So, my mom quickly learned that we had to have turkey so that we wouldn't be the odd ones out. But she didn't like it. She tried making turkey one year, and my dad was like, “What is this? This is so horrible.” But my brother and I loved TV dinners, because we were growing up in the 80s and TV dinners were a big hit. So, for Thanksgiving, my mom would just take us to the supermarket and say, “Which TV dinner with turkey do you want for Thanksgiving?” And we each got to choose ours with the little mashed potato and the steamed green beans that were terrible. And the buttered corn. That's how we got our turkey and it worked out for all of us.

I didn't really have to cook for myself until law school. I went to Stanford, and everyone lives on campus all four years because in Silicon Valley it's too expensive for students to actually live off campus. Law school cooking was very much boxed mac and cheese and Let's cut up some sausages and hot dogs and stick them in. I felt very fancy when I discovered Aidells sausages to put into my Kraft mac and cheese. I’d sometimes throw some broccoli in there, too.

I started cooking more in earnest when I was a lawyer. I was an attorney for six years. It was a little tough though, because I worked at a couple of really big international law firms, and the hours there are pretty bonkers. You show up in the morning at, like, 9am, and then you just don't know what time you're going home. It might be six or it might be two in the morning. If you're staying for dinner, you just order through the firm and your client pays for it. So, there was a lot of California Pizza Kitchen or whatever was on offer that night. And you always went out for lunch—at my second firm, they had actually catered lunch brought in every day. It seems like a perk when you're young, and then later you look back and you realize that's how they kept you there, working, all the time.

I would try to cook on the weekends because I was very, very into watching the Food Network. I've always been super into food and wanting to cook, so, before I started really cooking myself, I had already learned a lot just by watching cooking shows. I was always obsessed with food. When I was a kid, I remember going to the makeup counter with my mom, and as she's browsing makeup I'm going through the lipsticks and picking out the ones that are like “raspberry blush” or “blackberry ice.” Anything that referenced food, those were immediately my favorites. It didn't matter what the color was. There's this Taiwanese phrase, tam jia, and tam jia means that you're greedy for food, that you have this voracious appetite and you want everything. That was me. I was always tam jia. And it worked really well with my Chinese name, because the last part of my name was jia—and, so, my nickname was always jia-jia, which also means “eat-eat,” depending on what the tone is. So, that was kind how I tumbled into cooking.

Once I became a mom, then I had to learn not only delicious cooking but also super healthy cooking. So, that’s a new phase. We are super into eating a lot of plants now. If I cook rice, it's always either brown rice or a multigrain mix that I get from the Asian market that has brown rice, red rice, black rice, barley, millet, and quinoa. Sometimes it also has beans in it, depending on which brand I get. That’s always the base if I'm doing a stir fry or curry.

I love doing Thai curries now and just throwing in a bunch of frozen vegetables and cubed tofu, because it just cooks up so quick and it's so good for you, especially over that whole grain mix. At Asian markets, you can get these little tins of Thai curry paste—massaman is my favorite. I get one can of coconut milk (like 16 ½ ounces) and then I get a 20-ounce can of coconut cream, because it's slightly richer. You basically throw them all together into a pot, and it simmers and it's perfect. I also love throwing a dry rub onto chicken thighs and broiling them for 15 minutes and, at the same time, I roast a bunch of vegetables, like a sheet-pan meal.

I'm super into healthy-but-easy meals because during the day like I'm a working novelist. My days are full of either writing or doing publicity stuff. At the end of the day, I want to put something healthy on the table, but I also don't have a ton of time.

The first time I really wrote about food and books was in college. I had a paper due for a Russian literature class, and we were reading Anna Karenina, so I decided to write about food and culture and social class in the book, because the main character goes to a fancy meal in the city and he also has a meal in the country. And the meals are very much tied to Tolstoy's philosophy on life: the fancy food was overdone and too fussy, and in the country it was simple and it was pure. I mean, this is very Tolstoy, right? So that was my first foray into thinking about food together with literature.

Then later, much later, after I'd been an attorney, I started writing and I just couldn’t imagine writing a story without food. When I read a book, and the characters don't eat anything, it's like, But why? This isn’t actually a human being. You learn so much about authors based on what they choose to tell you about in their stories. For me, there's always, always food.

My first series, The Crown’s Game, was inspired by 18th-century Russia, so there's a lot of that same kind of food that I was talking about with Tolstoy, but my novel was a fantasy, so I could make it magical. I had these cream puffs that were shaped like swans, and they swam in a little pool of caramel. And in the second book, I had a French onion tart that may or may not have contained some kind of poison. You can take the idea of food and use it to build a setting or to do world-building.

Sometimes you can also use food as part of a plot device.

In my most recent novel, The Hundred Loves of Juliet, there are these Nutella cornetti that appear over and over again. And it's a window into a character. The Hundred Loves of Juliet is about Juliet, who is reincarnated over and over across centuries, and Romeo, who is basically lost in time. This goes all the way back to the original Romeo and Juliet, but the story in the book is set in the modern day. So, instead of “Romeo,” he goes by Sebastian Montague, and Juliet is “Helene”—and she doesn't know she's Juliet.

The food theme in the book is that Romeo always bakes these Nutella cornetti for Juliet in every single life that he finds her, because it's her favorite breakfast. Many things change about her from lifetime to lifetime, but one of the most consistent things is that she always loves having this for breakfast. So, he learns to cook. He’s originally from a wealthy family, and he doesn't know how to cook, but he learns how to do this for her. And then there are times in between their lifetimes where he hasn't found her, and he's alone. He spends years and years and years by himself, just waiting until the next Juliet is reincarnated, because he doesn't die. So, every morning when he doesn't have her, he still has this Nutella cornetti for breakfast as a reminder of this is why he's living. That is probably the best example I have from my books about food as a window into someone's personality.

Adding food like this is not a thought process; it just happens. When I’m writing, I will go on for too long about food and have to cut back. I've learned to self-edit now, but I have definitely had editors say, “Okay, this is great, but I think you're going to lose the audience.” And it's hard for me to understand that, because I think this is delicious and fascinating. Why wouldn't they want to know every single thing that's in the kitchen? But I get that not everyone's into food like I'm into food. So, I've learned that, as with any setting element, you have to limit it to a few sentences here and there. You can't do more than one paragraph about the food. You have to sprinkle it in throughout the entire story to get that feeling.

Food is one of the first things I think about for world building; I will forget about having to lay down physical things, like backgrounds and settings, but I will remember the food. My next book, which comes out at the end of July, is called One Year Ago in Spain. And in that one, I had so much fun with food, because the love interest is a Spanish artist and he loves cooking. When he moves to New York for a visiting professorship, his family packs him up with a binder of all their family recipes. And he woos the main character, Claire, by cooking on their first date. And she's kind of surprised, because he unpacks this picnic, and she's like, “Oh, where did you order from?” And he's like, “What do you mean?” And she's like, “Where did you get the food from?” And he starts listing the farmers’ market he went to and this little Spanish market that he visited, and she's like, “Wait, you made this from scratch?” And it's just such a strange concept to her that there's another culture where they value really the love that goes into cooking. And then they go to Spain, and everything else is set in Spain, so you get little bits of about Spanish food. It just makes me want paella and tapas whenever I think about that book.

More California Stories

This week the LA Times has a fascinating piece by Heather Sperling of Botanica (one of my favorite LA spots) explaining, in detail, where the restaurant’s money goes—with a striking result. Also, last week Illyanna Maisonet wrote about eating in the tiny town of Locke, which is one of my favorite little California spots because it is one of the few intact old Chinatowns in the region. (You can learn more about its history in this piece I wrote a few years ago.) And if you like the California wine scene (or are interested in inside-baseball-style stories about industry norms and debates), check out the SF Chronicle’s article about why Napa’s high-end wines are almost never discounted, the lengths wineries go to to ensure third parties honor the set prices, and whether these policies are ripe for change.

Photos: Courtesy Evelyn Syke (3), Georgia Freedman

Your Nutella cornetti turned out amazing!