Happy Tuesday! Apologies for the delay in getting this post out. It should have come last week, but the stunning recipe pictured below is hyper-seasonal, and for a couple weeks there, I couldn’t find any figs. (The buyer at Berkeley Bowl told me they were “gapping,” which is a fun new term to have.)

This gorgeous salad, and the wonderful story that goes with it, come from Laurence Hauben, a French immigrant who came to California in the early ‘80s and has been living in Santa Barbara for decades. She also spends some of the year in Placer County, where her boyfriend, Jeff Rieger, grows a variety of heirloom fruits at Penryn Orchard Specialties. While Laurence is not technically a chef, she does teach cooking classes in Santa Barbara. She’s also the reason the Santa Barbara farmers’ markets look the way they do today. About a decade ago, when she was the executive director of the farmers market association, she lobbied City Council to let vendors at the market finally sell dairy, meat, baked goods, and wine.

A couple of weeks ago (at the start of the overlap of plum and fig season) Laurence told me about how she learned to cook as a child in France, the shock she had when she first moved here, and how her cooking has evolved. Here is what she told me, edited and condensed:

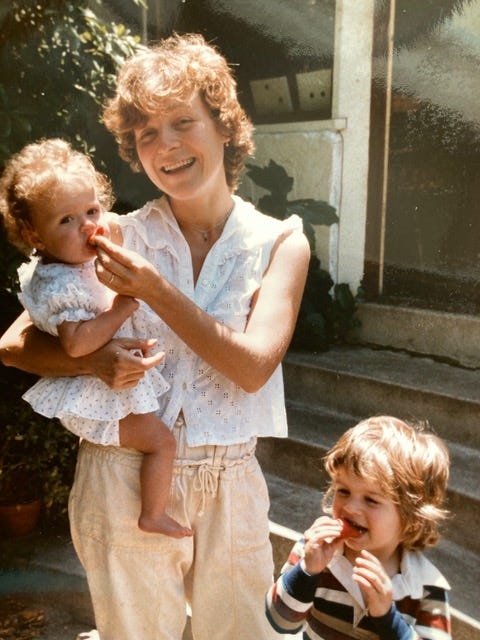

Laurence Hauben

I was supposed to come to California with a friend of mine, Philippe, who had been an exchange student with a family down in Laguna Beach. He and I had signed up for six-month program that was organized by the French government to teach people to work in the travel industry. Part of the deal was we were housed in these little bungalows on the French side of the English Channel, and I would cook dinner pretty much every night, just because I love to cook. Picture this: It’s a really dreary winter in northern France, right on the Atlantic, and it’s cold and miserable. And he said, “You know, we should just get out of here and go to California together. I have friends in Laguna Beach; they could help us get started. We could start a little catering company. You take care of the food, I take care of the customers. You’ll see, California is beautiful. You’re going to love it.” I said, “Great, let’s do it!” I was 24, and I spoke hardly any English, maybe 50 words.

So, we put our plans together—and then my friend fell in love. He was gay, and he met this gorgeous guy. We had our tickets for September 16th, and in June he met this man, and he said, “You know, I’m sorry, but I’m not going.” And I’m like, crap! Because I really had my heart set on coming to California. This is pre-internet, 1982, so I went to the public library, I found the phone number for the Paris bureau of the Los Angeles Times, and I called them and I asked them how to place an ad in the LA Times. I got the information, and it would cost thirty-four dollars (which was a lot of money to me) to place an ad in the LA Times. So I did, and the add said something like French girl, 23, looking for au pair job. And it said, Childcare, French cooking, light housework (I didn’t want to be stuck scrubbing floors all day long). And I gave an address where people could write.

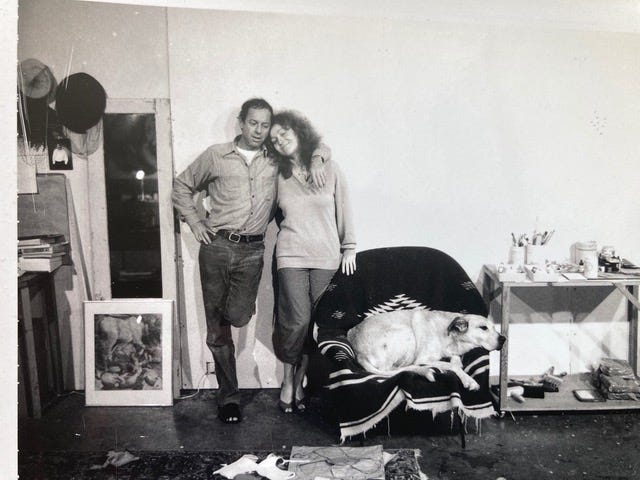

Summer went, and I just kind of hung out with my friends, and in August I called my mom for her birthday, and she said, “You have all these letters from America!” I had twenty-six replies to my ad. They ran from wealthy people in Bel Air to teachers in the San Fernando Valley to lonely guys in Venice Beach. And there was this one letter that really stood out, because I liked the handwriting—it was cursive—and was a beautiful, warm-hearted letter. There were two photos in the envelope: one was the husband and wife smiling and hugging each other in the garden, and the other was of their little baby boy, who had enormous blue eyes and blond curls, and he was in the swimming pool with his little arms going Please pick me up. I was a great shot. And I went That’s where I want to go!

So I called, and the wife spoke a little bit of French, and I spoke a tiny bit of English. I told her I had my airplane ticket, and she said “Wonderful.” And then she asked me how much I wanted to get paid, and I said (I had no idea what the cost of living was in California, but I knew I would have room and board), so I said, “How about fifty dollars a week?” And she said, “Great, you’re hired.”

And so that’s how I came to LA. And Larry, [my daughter] Julia’s dad, was one of their best friends. He lived here in Santa Barbara. And we met, and fell in love, and that was that.

In the family where I grew up, everybody knew how to cook. It’s like knowing how to wash your face. It’s like knowing how to brush your teeth. It’s like breathing. It’s just something you know how to do. It’s just like, you’re going to need to eat three times a day, so you’re going to need to cook three times a day.

My mom did most of the cooking, my dad did most of the baking, my grandfather on my father’s side was the jam maker, my grandmother on my mother’s side as the hostess for all of the holiday gatherings, and food for all of the holiday gatherings was cooked together. I can’t remember not knowing how to cook. It’s that ingrained. I think my first job was probably shelling peas when I was three years old, and then learning how to wash a head of lettuce. By the time I was five, I could make mayonnaise and I could make a salad dressing. We used to have contests on who could peel and apple without breaking the ribbon—you know, you take a paring knife, and you go around and around and around and around.

I’m from the very northern tip of France. There’s a big city called Lille, and there’s a smaller city of about 1,000 inhabitants called Tourcoing, and it’s right on the Belgian border.

The local food? French fries, definitely. Because French fries are really Belgian. You know, the best French fries are in Belgium and in Northern France because they’re fried in beef tallow, and they’re fried twice. There were leeks, shallots, potatoes, beets. There were things like lamb’s lettuce and Belgian endive.

It’s a very working class, industrial area. There’s not a lot of farmland right around where I grew up; it’s very much a large metropolis. And it never felt like home to me. It rains all the bloody time. I remember getting on my knees and praying to baby Jesus that the rains would stop so I could go play outside. We had a little vegetable garden in the backyard, so we had little radishes and shallots, little carrots and things; basic stuff. But it was always fresh.

Both my parents were partially orphaned. My mom lost her dad during World War II. My father lost his mother when he was 14. And both of them had to go to work in factories at age 14. I grew up in subsidized housing, public housing. I never ate in a restaurant in my entire childhood. There was nothing about food that spoke of privilege. But all the food we ate was fresh, it was real, it was homemade. There was no margarine, it was real butter. My mom used to say, “I’d rather give my money to the baker than to the doctor.” Which is I’d rather spend my money on food than on medicine because I ate crap.

Because both my parents worked full time, I ate at school. The French school day, for grade school, went 8:30 to 11:30, and 1:30 to 4:30. And from 11:30 to 1:30 was lunch. The cafeteria food was nothing like what you have here. The little kids ate first, and you went down, and you sat down at tables of eight, and you got a three course meal served to you by the lunch ladies. So, you’re not standing in line with a tray, you’re sitting down to a proper meal. They’d start you with either a soup or a salad, and then a main course, and then a little dessert. That was a cookie or two, or a piece of fruit, or a little yogurt. And, again, all the food was made there, by hand, by the lunch ladies.

I talk about enjoying life one bite at a time. When you’re poor in France, good food is your one luxury, I think. So that’s how I grew up. We didn’t have money for tennis lessons or ski vacations or anything like that, you know? We had money for quality food and for shared meals. And the companionship of shared meals.

My first morning in California, I wake up, and, first of all, I expected all the California kitchens to be super modern. I expected everything about this country to be hyper-modern and automated. And I walked into that kitchen, and they had a stove that dated to the 1930s, one of those giant O’Keefe and Merritt stoves. And that was like, Wow, you guys are behind! And then the bread came in a plastic bag. I put it in the toaster, and I spread it with butter. And I took a bite, and I couldn’t taste the butter. I was like, huh. So, I put more butter on the bread, and I tasted it again, and I couldn’t taste the butter. So, I took a piece of butter, and I tasted it, and all I could taste was salt. I couldn’t taste that little nuttiness that I was used to in French butter. And I was like, Oh. This is going to be hard.

And then the first trip to the supermarket—there was a move that came out in the early ‘90s called Green Card, with Gerard Depardieu, and there’s this scene where he’s in the market smelling the melons, and they have no smell, and he’s putting them back—that was me. I went to Ralphs and I’m walking through the produce aisle, and all the produce looks like it rolled off an assembly line. All the apples are identically sized, and they’re perfectly glossy, and everything looked so weird, and nothing had any smell.

Then you go to the meat department, and nothing looked like an animal. Everything is in these little styrofoam boats, shrink-wrapped, pre-cut. And the seafood section, same thing; there’s not a single whole fish to be found. In France, people want to see the head of the fish, because that’s how you tell if a fish is fresh—you look at the gills. And if the gills are brown and slimy, you know the fish is old. When all you can see are filets, there’s no way to tell. (Well, you can actually tell, but it’s harder.) So that was a little discouraging.

I had this kind of a funny moment: I was only making fifty dollars a week, Christmas is coming, and they had an orange tree in the backyard with beautiful oranges. I thought, Ooo, I know what I’ll do for Christmas presents for the family, I’ll make chocolate-covered oranges. Ok. I need some dark chocolate. I didn’t drive, so Rick, the husband, and I go down to Ralphs, and I’m looking at the chocolate aisle. You know, in the French chocolate aisle in any supermarket, even in a little convenience store, you’re going to have fifty feet of chocolate with different shades. I’m looking, and it was pretty slim pickings. I’m looking for dark chocolate, and I just wasn’t sure what to buy, so I bought something that said, “dark chocolate.” So, we pay for it, and we get to the parking lot, and I open it—like any girl would do—I open the chocolate bar, and I take a bite. I spat it out, and I literally had a meltdown right there in the parking lot. I went, “You’re the richest country in the world, and this is what you call chocolate? Are you f-ing crazy? What’s the matter with you people? Where am I? I might as well be in communist China!” I had this total meltdown.

It was nighttime, and so we drove home with me very upset and Rick thinking that I was going to just fly home the next day. The next morning, he drove down bright and early to Beverly Hills, and he came back to the house with something that looked like a gold ingot that he had bought (probably at great expense, at some fancy shop in Beverly Hills) that was imported dark chocolate so that I could make my chocolate-covered orange peels. They were wonderful people!

I moved to Santa Barbara in the spring of 1983, and I got to plant a little vegetable garden. My brother came to visit and brought me some seeds of mesclun. I went and found out who the fishermen were. I could tell there were fishing boats, but that food was not at the supermarket. So, I started to develop an alternative network of providers. I would go to the harbor, meet the fishermen, make friends. And then I found the farmers’ market, which was really small at the time, but that was real food, so that was great. There was the Santa Barbara Food Co-op; there was a health food store called Follow Your Heart. And then the wonderful thing about California is how multi-cultural it is. So, I discovered Mexican food.

The big thing that I realized, soon enough, was that if you were rich enough in this country, you could eat as well as anybody in the entire world. But if you were not rich, you were expected to live on stuff that I wouldn’t feed to my dog and that nobody in France, including in my totally working-class public-housing family, would consider food. And that’s still how I feel. Good food should not be a luxury. It should not be something that’s only accessible to wealthy people. It’s a human right. And to me, an enormous part of the health crisis in this country has its root in the fact that most people don’t have access to simple healthy food and how to cook it.

Using local ingredients always makes sense. Because you want to cook with the seasons. You’re not going to want to eat the kind of heavy food that would make sense on a cold dreary day in Flanders when it’s 82 degrees and sunny here in Santa Barbara. So, getting to know local farmers, getting to know all the different cultures that make California what it is, and incorporating that in how and what I cook has just been so much fun.

The thing that’s definitely French about the way I cook is the way I approach ingredients. I have no fear when I encounter a new ingredient. Because it’s like when you learn to ski as a child—you’re not afraid, because you’re a kid. And it’s kind of like that. I’ll talk to chefs here, and they’ll have this fabulous seafood restaurant, and the most popular item on the menu is the burger. That’s what people are familiar with, and Americans tend to reach for what’s familiar when it comes to food. If you present something on the menu that they haven’t seen before or eaten before, they’re going to be reluctant to try it. They’re going to be afraid. If you’re from France and you see something you’ve never seen before, it’s like it’s a new toy to play with.

What do I cook? It’s summertime, so I will be eating a lot of ceviche. I’m going to be eating a lot of salads. I’m going to be doing just some simple sautéed vegetables. I eat a ton of vegetables; morning noon and night there’s vegetables on my plate. There’s a lot of flavor, not a lot of sugar.

I was making myself a salad today. Yesterday I made a batch of salad dressing. (That was one of the first thing that blew me away: There was a whole aisle of bottle salad dressings in American supermarkets. I went What the heck? You guys don’t know how to make a salad dressing? That was one of the most ridiculous things to me and still makes no sense. It’s so easy. You just shake it together and put it in your fridge and you have it for five days. It’s a lot better and cheaper.) So, I had some basil, garlic, some good olive oil, salt pepper, and some balsamic vinegar and just shook it together. That’s in my fridge, it’s ready to use. And I had some beets I got at the farmers market, so I diced them and steamed them. I have some toasted pumpkin seeds that I seasoned with a little cumin and cayenne pepper, and some fresh chèvre. And I was going to have that today. Really simple.

Typically, I go to the farmers market twice a week, and I see what looks good. Right now there’s some cut-up watermelon and cantaloupe in my fridge—the first watermelon and cantaloupes are in, so I keep them chilled. There are chilled plums, (Santa Rosa plums) and some fresh figs that I brought back from Jeff’s orchard, and some Blenheim apricots. I’m making apricot jam and fig jam and plum jam.

Nothing going to waste is really important. And that’s the way I was brought up, because we couldn’t afford to waste anything. So when I, let’s say if I roast a chicken, I don’t throw away the bones when my plate is empty, I use the bones to make chicken stock. And when I buy fish, I use the bones to make fish stock. When I’m at the farm and there’s a ton of fruit, that’s when I make jam, or we freeze the pulp, or I make apple sauce, and I make pear sauce. In the fall we make hoshigaki. We just try to use everything.

I eat some meat and some seafood, but not a ton of it. A lot of time I’m perfectly happy with a vegetarian meal, especially if it’s just for me. It’s easier. I got some beautiful duck eggs from the farmers market; I love duck eggs. So yesterday, when I made lunch, I did a couple of duck eggs over easy, fried in olive oil, on top of my salad. That was really lovely.

It’s just playing with food, basically.

Arugula, Plum, and Fig Salad with Ricotta and Plum-Shallot Dressing

This is a seasonal salad that Laurence whipped up, with the ingredients she had in her kitchen, just a couple weeks ago. It’s fantastic as it’s written, but Laurence likes to emphasize that you should use what you have in your kitchen, and experiment, rather than always following recipes. The thing I love most about this dish is that it has a phenomenal salad dressing that uses plums as the acid component, which give the salad a lot of added flavor. Laurence also makes her own ricotta, because it’s very simple to do; there’s a recipe below. A good quality ricotta like Bellwether’s will also work well.

Serves 6

6 cups arugula

1 pound Santa Rosa Plums (or similar)

6 ripe figs

3 tablespoons minced shallot

½ cup extra virgin olive oil

Coarse sea salt

Freshly ground pepper

2 tablespoons minced parsley or basil

1 ½ cups fresh ricotta (see recipe below)

½ cup crushed roasted pistachios

Wash and drain the arugula.

Make a plum puree: Pit ½ pound of the plums and place them in a covered saucepan over medium heat until they soften, about 8 minutes. Place the softened plums in a blender and process until smooth.

Place the shallots and olive oil in a small saucepan and sauté until the shallots are golden.

Transfer ½ cup of plum puree to a bowl and season with a scant teaspoon of salt and a few turns of pepper. Whisk in the olive oil-shallot mix, then add the parsley or basil. Taste the dressing and adjust the seasoning as necessary.

Slice the remaining plums and your figs. (I like to slice my plums so they look like flower petals and cut the figs in 6 wedges.)

Dress the arugula, then mound it on plates and sprinkle it with the crushed pistachios.

Scoop ¼ cup ricotta into the center of each plate. Surround it with the plum slices and fig wedges.

Spoon a little additional dressing on the salad and serve.

Homemade Ricotta

Make ~2 cups

5 cups whole milk

1 cup heavy cream

2 tablespoons lemon juice

½ teaspoon salt

Set a large sieve lined with a damp flour-sack towel or two layers of damp cheesecloth over a bowl.

In a saucepan, heat the milk and cream to a boil.

Add the lemon juice, reduce the heat, and stir for a couple of minutes, until the milk curdles.

Turn off the heat, add the salt, and let the mixture rest for 10 minutes.

Strain the mixture; the whey will be in the bottom of the bowl, and the ricotta will be in the cheesecloth.

Use right away, or refrigerate. Ricotta is best eaten within 24 to 48 hours.

More California Stories to Read, Watch, and Listen To

In the last couple weeks, I’ve really enjoyed Eater LA’s piece on restaurants repurposing old fast food buildings; Word of Mouth magazine’s piece by Sally Schmitt’s granddaughter, Polly Bates, recalling her grandparents’ life and accomplishments through a very personal lens; and the great NY Times piece about San Ho Won that came out yesterday. And, while it’s not about California, the piece on Morning Edition about farmers in Colorado being paid to stop pumping water is extremely relevant to California food systems.

Photo: Georgia Freedman, courtesy of Laurence Hauben (6), Georgia Freedman

Another lovely interview!