Sheer Khurma, French Pastries, and Other Ramadan and Eid Traditions

An interview with Faheem Chanda of Oakland

Lovely Readers - Apologies for the late posting this week; it’s been a doozy! (Check out the More California Stories to Read, Watch, and Listen To section at the end of the post for info about some other CA-based food work I’m currently doing!)

This week, I’m sharing a conversation with Faheem Chanda, an Oaklander who works in tech sales and is also developing a new kind of kitchen appliance on the side. Faheem told me about how he came to California as a teenager, how he and his wife, Amanda, and their kids usually eat during the week, and how the family observes Ramadan and Eid. He also shared his mother’s delicious recipe for Sheer Khurma. Here’s our conversation, edited and condensed for clarity:

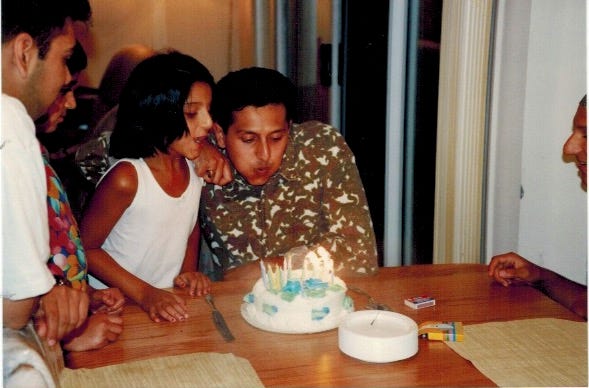

Faheem Chanda

Both sides of my parents’ families are from a particular state in India, Gujarat. My understanding is my mom and my dad’s families were in neighboring towns. During the partitioning of India and Pakistan, the communities of their towns emigrated to Pakistan.

So, my mother was born in Pakistan, although all four of my grandparents were born and raised in Gujarat, in India. I identify myself as somebody from Pakistan, for a lot of reasons, but that is my ultimate place of origin and home.

After immigration opened up for folks from Asia and other parts of the world in the 1960s, some of my mom’s and dad’s siblings decided to emigrate to America. My mom’s older brother moved to California, and he’s lived here, I think, since 1969. My father had some brothers that moved to Florida, and he also had a brother who moved to California for some time to go to Cal Poly to get a degree in aerospace engineering. So, I visited California several times as a kid.

I was born in Pakistan, but my parents lived in Dubai at the time. My mother wanted to be with her family her family for my birth, so she went back for that. I think for six months to a year-and-a-half I lived in Dubai, then from Dubai I went to Germany. I lived in Germany for a couple years, and then I moved to France when I was three or four.

My dad worked in finance. He was an accountant, and his company shipped him off to places. When I was seven or eight years old, they were going to ship him off to Gabon, in Africa. So to continue our educational path for my sister and I, my parents sent us to a boarding school in the U.K. I lived in the UK from about eight to ten, and then I moved back to France at 10, and then I lived there until I was 17.

I speak French, and I speak Urdu. I learned a little bit of Arabic, and I tried learning Italian when I was in my 30s. My parents’ mother tongue—which is a subset of a language from Gujarat—I understand that, but I can’t speak it. I love languages. We hear a lot of different languages in California; I wish they would teach more in schools.

When I had just turned 17, I was just about to enter my last year of high school—or the equivalent of high school in France—and my parents said, “Hey, it’s time for you to go do something with your life. Get on that plane with your suitcases, you’re going to go live with your uncle for a year.” I lived in Milpitas and went to Milpitas High, and from there I went to De Anza College and worked my way into attending San Francisco State for my bachelors.

When I was growing up, my mom made a lot of the foods of her childhood. But when you have kids who grow up in a different place, the children pick up the local foods and customs. So, pizza was my favorite food—it probably still is in many ways. American food like McDonald’s which was sort of kind of common in France—or not common, because the French like their own food, but popular. At home, there was a lot of traditional Pakistani food, and then occasionally my mom would make like pasta or these different French stewed chickens or things like this.

The school that I attended actually provided lunch, so that was a mix of all different kinds of foods. Also, the foods that I had in boarding school were very English; there was a lot of shepherd’s pie, mashed potatoes, things like this. My father would tell me, “You have no idea how lucky you are.” And I would think, “There he goes again, lecturing me about something.” It’s only now, as an adult, that I realize that, wow, I had a really broad exposure to foods.

And California has its own kind of twist on things, which I think is really interesting. What I love about the food over here is that there’s a lot of fresh ingredients. Because California produces a lot of the foods for the rest of the country (and for other parts of the world), we really get a lot of the best produce and a lot of forward-thinking cuisine, which is really exciting.

I’ve cooked a little less since I’ve gotten married, but I used to try to make a lot of different things. I used to make a lot of Pakistani food, and then I experimented with Italian food, because I spent a lot of time in Italy with my sister, and I love Italian cuisine. Then my overall situation evolved, because I became diabetic, so I had to change my cooking to be a lot more focused on low-carb, high-nutrient, nutrient-dense foods.

Amanda cooks a lot of what I’d call traditional California-type cuisine, with a mix of some Italian. And my kids love Mexican food, so we make we have Taco Tuesday nights, and we have Meatless Mondays, because my wife is vegetarian. So, we eat traditional Pakistani and vegetarian foods; my kids love burgers and pizza, so they get a lot of that; and then, if we want good, authentic Pakistani food and we don’t have time to cook it, we usually order that in. We also go to a lot of different Middle Eastern restaurants, and there’s a lot of that in Oakland and in the greater Bay Area. So, we get a lot of different kinds of food.

I do a lot of cooking for myself, because it’s not necessary for my kids to eat that way [following a diabetic diet]. I tend to eat twice a day with a couple of mini snacks in the middle. My first meal is around 11, and I’m doing a very California-style breakfast: we’re talking a lot of greens in an omelet—kale, poblano peppers, broccoli, spinach, three eggs, some cheese, with some avocado. And I might spice it up either with some Mexican salsa layered on or by sprinkling in some fresh herbs—some dill, some parsley, some rosemary maybe—just to give a little more flavor to the eggs. And then for my side I’ll have a mix of berries. There’s nothing better than some California raspberries and blueberries, maybe mixed with some whipped cream.

I’ll have a collagen powder protein shake around 3 or 4, and then for dinner it really varies. I’m cutting back my meat consumption to maybe two or three times a week, so that would be either grass-fed beef or some free-range chicken—or we’ll try to do fish once or twice a week. On Tuesdays, when we’re doing the taco night, I’m using almond taco shells instead of the traditional ones (I kind of cut back on the corn) and then the kids will have the regular ingredients in their tacos, like chicken. Since Amanda’s vegetarian, there will be a lot of beans that she mixes with quinoa and tomatillo sauce, so it tastes really nice in the taco. Fridays is usually pizza night. And then we’d have maybe one or two night when we’d go to eat out. So, if you look at the week, there’s this pretty broad range of cuisines.

Of course, this is not how I eat during Ramadan.

If you look at Ramadan, what you’re seeing on the surface is that a human being is not eating from dawn to dusk. Now if you kind of unpack that, and you go, What else is going on with this person? what you’re really doing is something else. The way we see it, is you have the human soul, and the soul has all of these different layers. One of these layers is what the called the nafs. The nafs is your ego—it’s that very powerful component of who you are that drives you to make certain decisions, good decisions and bad decisions. And what you’re really trying to do is, you’re trying to tame that part of your soul to be more relaxed, to be more in tune with scripture, to be more in tune with everything around you.

So, you’re not eating, and you’re not doing a lot of other things too. You have to bring your behavior to the point where it’s very scaled back. It’s like spiritual fasting and physical fasting, is I guess what I’m trying to tell you.

To do that, we sit down with our kids and we make a plan: What’s my goal? I’m going to read X amount of a religious book. I’m going to try to do all my prayers at the right time. We’re going to learn about this topic in our religion. Our goal is for the kids to be more comfortable with this and wanting to participate as they get older.

For young kids, [fasting] is discouraged. Their brains need the glucose in the food. Around the age of six, seven, or eight, we start suggesting that they do like a fifth of the day. And then you say, ok, do two-fifths of the day. And then from lunchtime to sunset—which is pretty long; it’s about seven hours. Last year my kids did two full fasts; they had a couple days when they wake up and have breakfast around nine and then fast until the end of the day. Those are hard days still. And then they’ll do a few from lunch to sunset. And then several from three or four o’clock until sunset. So, you kind of ease the child into it. Around the age of fourteen, fifteen, sixteen, many kids are doing this all day, while they’re going to school.

To the outside person it looks difficult, and the first couple of days are, and then you’re just kind of in the flow and you just go about your day.

Many families come together to open their fast. That process is called iftar. It happens at sundown, and then after that, they all go to the mosque to do the evening prayer. So, there’s a combination of some social activities and a lot of spiritual activities, and it’s a time of reflection. You’re really conditioning your body and your spirituality for the next twelve months to come, when you’re going to need all that momentum to go through and face all the challenges of life.

I think if you have two households that are very close by, it would be very common to see two families cooking together for the broader family. In Pakistan, it’s actually very common for your neighbor to bring you a dish every night or for you to take it to their house, and then to the third neighbor and then the fourth neighbor, and pass different things to people in the neighborhood every night. I see less of that in America, but what you’ll have in America is more people just going to other people’s houses for the iftar, or they’ll go to fundraisers, or they’ll go open their fast at the mosque, because the mosque will provide meals to underserved communities or maybe folks that are traveling and need a quick place to go get a bite to eat.

I think that the recommended food to open your fast is a date—a couple of dates and some water. Then, for your next plate, you have (at least in South Asia and the Pakistani-Indian community) a lot of sweets, a lot of fried foods. You might have some kebabs. It varies by community, because the Somalis may do it differently than the Pakistanis who might do it differently from the Jordanians, who might do it differently from the Saudis. But opening with a date and a glass of water, that’s almost a universal thing.

But these are lighter meals, because what’s going to happen is, you’re going to have a small meal, just to open the fast, then you go do your prayers, which is right at sunset, and then you have your full meal. It gives your stomach a chance to absorb what you just ate without over-stuffing yourself, and then you go have your real meal.

I would not say that every night is an elaborate meal, because most people are tired and they’re trying to focus their energy on the spiritual things as opposed to the food. But once or twice in the week there might be something elaborate that you might do with your friends or extended family. I’m visiting my sister’s this week, and last night there was the dates, obviously, then there was some almonds, some cashews, some pistachios; there was a fruit bowl, there were some samosas, and then some other kinds of appetizer-like things. And then dinner was actually quite European: there was mussels with pasta, and my sister also made a fish biryani.

The end of Ramadan is called Eid; Eid literally means “celebration,” and this particular one (there’s two Eids in the Muslim calendar) is called Eid al-Fitr. It’s celebrating the end of Ramadan, and it’s usually a giant feast. There’s a morning prayer—that’s part of the tradition, there’s a communal prayer—and after that, people go party and they enjoy themselves, eating and fulfilling some of those culinary desires they may have had in that last month.

But I can tell you that on that last day, it’s kind of bittersweet, because there’s a lot of other blessings within the month that you get to participate in, and you get rewarded for taking on this task. Coming into it is a moment of a lot of excitement, like Here comes Ramadan! And it’s emphasized strongly as a communal effort. So, when the month ends, people are actually quite sad.

For Eid, my wife and kids and I have this very California-esque tradition. We’ll go to our morning prayers, the communal prayer—there’s a sermon, and you celebrate with community—and then we go to a bakery we love in Berkeley, Fournée, and we get all sorts of baked goods. Then we’ll come home and make a very elaborate brunch. The last couple years during Covid, you were not able to invite folks over, but we usually have five or six other families over for brunch. And around 1 o-clock we’re pretty exhausted, so there’s a little nap or rest time, and then we’ll go for the evening festivities.

Since my uncle (who I lived with for a year when I moved to California), lives in San Jose, I have some extended family there. We’ll do a house tour and go say hi to everybody, give them their presents, get their presents for our kids. We just try to make it as rewarding and fun and festive as possible.

I have an aunt that usually holds an Eid party, and we go there. She usually has seven or eight dishes, all homemade. Biryani’s one, and there will be two or three vegetarian dishes—usually a dal, a chana, and maybe vegetarian samosas—with two or three meat dishes, such as a nihari and a chicken korma. It’s usually a big elaborate event. She probably has 30 or 40 families at her house. It’s a big deal. I look forward to that every year.

Sheer Khurma

This is a dish that some families traditionally make on Eid, before morning prayers. It’s similar to a rice pudding but is made with tiny noodles, almonds, pistachios, raisins, and cardamom. This version is Faheem’s mother’s recipe. It looks pretty elaborate—skinning the nuts might sound laborious—but it’s actually relatively easy to make, and the sweet, nutty, cardamom-scented flavor is totally worth the work, whether you have it for breakfast or for a snack or dessert later in the day.

Serves 4

⅓ cup whole almonds

½ cup shelled pistachios

4 ¼ cups milk

1 cup half and half

¼ cup butter

1 cup Pakistani vermicelli (sold as “roasted vermicelli”)

4 cardamom pods, split, seeds removed and husks discarded

¼ cup raisins

⅓ cup sugar

1. Put the pistachios and almonds in a pot, cover with water. Bring the pot to a boil, and boil the nuts for 5 minutes; drain. Peel the skins off the pistachios and almonds, and then chop the nuts into small pieces.

2. Put the milk and half-and-half into a pot large enough to hold all of the ingredients. Bring it to a boil, and boil until the liquid reduces by 15 percent, about 20 minutes from the start of boiling. (If your pot has a hotspot and the milk is sticking, make sure to scrape it to keep the milk from burning, which will affect the flavor of the whole dish.)

3. While the milk is boiling, heat the butter in a large skillet over low heat, and gently fry the noodles for 5 minutes. Add the cardamom, raisins, and chopped nuts to the pan and mix to combine.

4. When the milk has reduced, stir in the noodle-nut mixture. Cook until the noodles have softened fully, 5 to 7 minutes. The texture of the milk should be like thick cream, rather than pudding.

More California Stories to Read, Watch, and Listen To

If you want a look behind the scenes of a working California cattle ranch (and some great recipes), check out my friend Elizabeth’s show Ranch to Table on the Magnolia Network; it now has two seasons streaming on Discovery+. (And look for the cookbook I’m co-authoring with Elizabeth fall of 2023.) If you’re looking for more recipes to make this week, Ben Mims (who was recently nominated for a James Beard Award!) mashed up Southern and California traditions to create a fun shrimp boil for the LA Times this week, and Jessica Battilana, who is leaving her column at the SF Chronicle after eight years, made a butter cake with strawberry-rhubarb filling as a farewell. Lastly, if you want something fun to listen to, KQED reported on the California origins of Indian sizzlers, and Good Food on KCRW did a piece on the Skirball Center’s upcoming exhibit on Jewish delis, which I might just have to drive down to LA for.

Photos: Georgia Freedman, Courtesy of Faheem Chanda (4), Georgia Freedman