Lessons From the Heart of California's Slow Food Movement

An interview with Fanny Singer of Berkeley and Echo Park

The last weeks of August and the first weeks of September always feel like the ideal time for simple, ingredient-forward dishes. I thought this period would be the perfect time to share my conversation with Fanny Singer, the founder of the Permanent Collection design company, author of Always Home: A Daughter’s Recipes and Stories, and daughter of Alice Waters, the chef who helped kick off the Slow Food movement.

Fanny and I talked about what food meant to her when she was growing up, how her cooking differs from her mother’s, and how food works itself into her career. I was particularly moved by the fact that we were having this conversation on the eve of Fanny’s own transition to becoming a mother, and, while we didn’t talk about it at the time, I can’t help thinking about how she’ll pass this approach to food on to her own child—and how her cooking may continue to change in the process. (As a parent myself, I found the section in Always Home about what Alice packed in Fanny’s school lunches both inspiring and somewhat demoralizing.) Last week, I shared Fanny’s recipe for eggs smothered in herbs. For this week’s newsletter, she shared a wonderful recipe for roast carrots, which you’ll find at the bottom of the post. But first, our conversation, edited and condensed for clarity:

How long have you lived in LA?

It's been just under two years now. I moved down during the pandemic. Until the beginning of July, I was in this really sweet little Rudolf Schindler-designed apartment from like 1929. We just moved into a house in Echo Park. I'm pregnant, and the apartment that I had was under 600 square feet. So, we have found slightly roomier accommodation.

What was food like, when you were growing up?

Meals always felt really like a moment of togetherness. It was a moment of community. Sometimes they were at the restaurant, which was always bustling with friends and acquaintances and people who’d come through Berkeley to perform at Zellerbach or for a concert in San Francisco. Chez Panisse was this kind of nexus for culture in the East Bay. And so I had the experience of being in that institution and having that proximity to the power of gathering. And then at home, too, our family ate together every night, and there was always an invitation to friends to drop in—an open-door policy, an extra chair—and there was always enough food for one more. That was the kind of philosophy that prevailed.

I think we all know that I was eating delicious food. It almost doesn't bear repeating. So, in a way, I think the most kind of salient association is that eating was also about gathering.

By the time I was on the scene, Chez Panisse had been around for nearly 13 years. So, my mom was not cooking on the line anymore at that time. She was going to the restaurant every day, but she was not away in the evenings. She was always home. So, I really feel like I did not have the kind of deprived child existence of a kid whose parent is beholden to a typical restaurant service. And Chez Panisse also has a very unorthodox structure in terms of the culinary hierarchy in the kitchens. There are two chefs for upstairs but two chefs for downstairs. So even the ones who did have small kids who were working these hours that were more punishing, it wasn't necessarily all the time. They would rotate, like three days on and three days off. The restaurant was always set up in a way that I think was more humane for people's lifestyles and families.

Did your mom teach you to cook when you were little, or was the kitchen her domain?

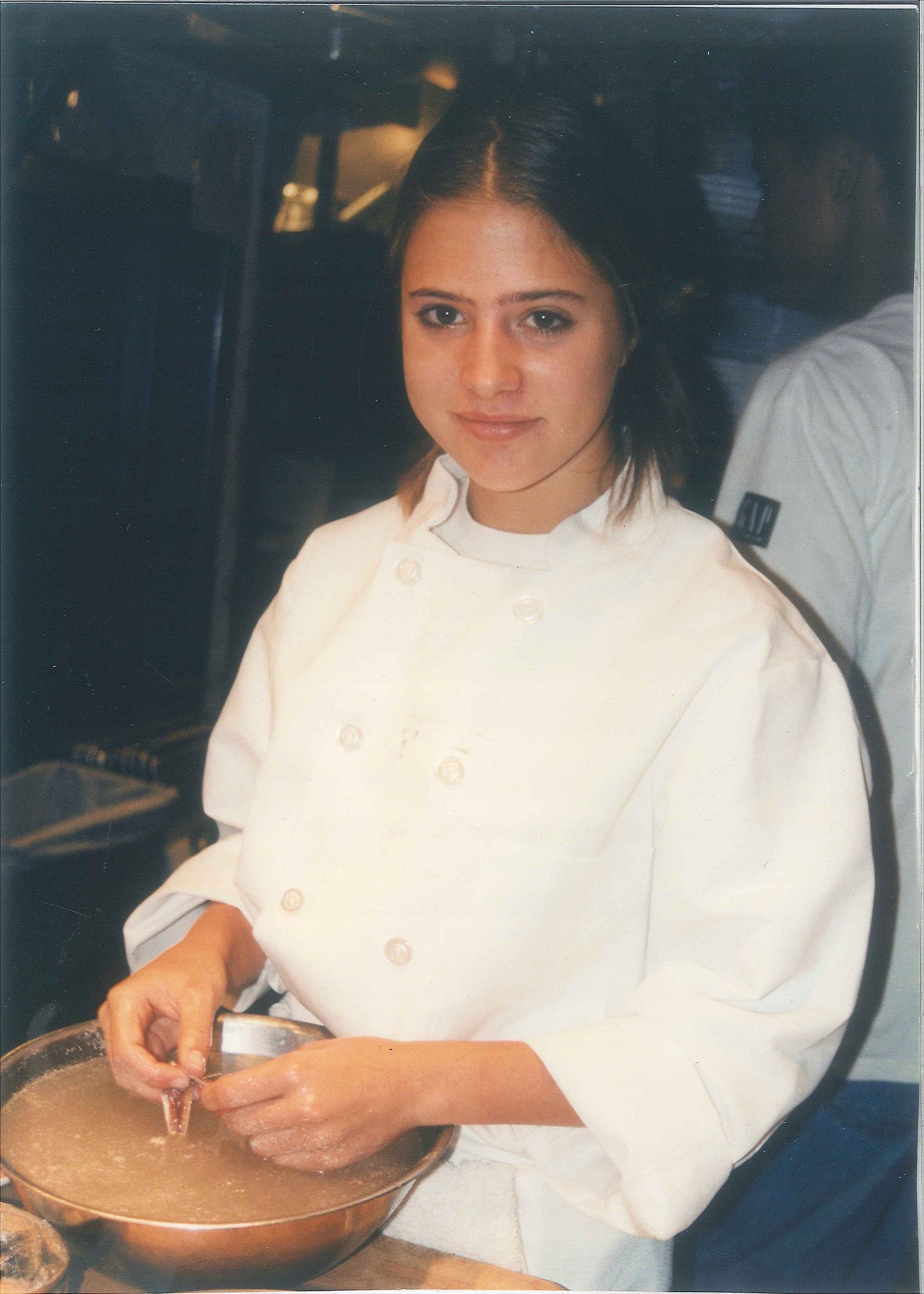

More the latter, actually. It’s not like I was excluded. My mom did teach me little tasks, like we would peel fruit, and we would top and tail beans, and we would shell peas and stuff together. But I didn't really, really learn to cook until I started working at Chez Panisse in the kitchens when I was a young teenager. I worked there summers and longer school breaks. When I was in college, I would spend winter break working as a runner in the kitchen or in the salad department or sometimes on the floor, too, doing some bussing or waiting.

Did you ever think that that’s what you’d do with your life?

Never once. I think I really understood, from quite early on, what it took to do something to the standard that my mom had undertaken with Chez Panisse. It was a complete labor of love. And I had too many other intellectual distractions. I liked to cook very much, but I ended up getting a PhD in art history. So, clearly, I went way off-piste as far as my gastronomical career. But I found my way back to it in writing about food and cooking so much at home; now I feel like it's as much part of my occupation as anything else.

How do you distinguish between the food that your mom created for Chez Panisse and what she was cooking at home? Were there differences, or was it essentially the same kind of thing, just an extension of her creativity?

It was pretty continuous, I would say. But I think that's always been the culinary ethos at Chez Panisse. My mom always wanted it to feel like you were going to someone's home and having a fabulous meal. And I still kind of feel like that. The general atmosphere and quality of the food is that it's not technically, obscenely challenging. There's not equipment that you would never have in a home kitchen or ingredients that you would never be able to source. It’s a very honest, kind of transparent culinary methodology. She wants more people to cook at home and to cook in that way, to use delicious and real and regenerative and sustainable ingredients.

What were some of the staples of your childhood?

We had salad at every meal—I mean, maybe not always at breakfast, but sometimes—but definitely always at lunch and always at dinner. It was an expected part of the repast, always. And it's something that I really have carried forward in my own cooking.

My mom also had this hearth constructed in our kitchen, this really beautiful, elaborate hearth that had a pizza oven on one side and then a big open fireplace with a rotisserie and a space for a kind of Tuscan style grill. And, so, there was often a fire. You know, it's Northern California, so it’s always chilly in the evenings. There's often a fire going in that hearth, and usually some element of the meal was cooked in there. Because it was used to kind heat the home, which didn't really have central heating. So, you could grill a little bread or maybe a piece of fish wrapped in the fig leaf, or a vegetable; or maybe it was even peaches grilled on fig leaves for dessert or something like that.

How did your approach to food change as you started cooking for yourself? Is your style different from what you grew up with? Are there ingredients that you've added or things that you feel drawn to in your own cooking?

My experience as a kid growing up in the state of California is that there was no California cuisine. I mean, there was something that was being called that—you know, it was like sort of the 1990s’ California nouvelle cuisine that I associate with, say, Wolfgang Puck. I ate so much of what, at the time, would've been called “ethnic food”: so much Mexican food and Vietnamese food and Chinese food. The rich and dense cultural histories of the Bay Area—especially around Mexican and Chinese culture and those food traditions—meant that there was a lot of really interesting flavor exploration that I was able to undertake, even as a high school student. I was exposed to so many herbs and so many chilies and spices that my mom is just much less at home cooking with. Her tradition of cooking really comes out of her time in France, in the ‘60s, which is a wonderful culinary heritage. But I really thrill to the use of herbs and chilies. I basically can't get enough herbs and citrus and spice into food. My sort of default place is to work in a pretty maximalist way with full, fresh flavor profiles.

So, when we're cooking together, I'm pushing it in that direction. I'm like, “I want more lime, more chile.” And my mom—especially because we were together for the first 10 months of the pandemic—she really did start to adapt to my cooking style more. She got into putting lemon zest on everything to finish it (or wherever it was actually appropriate). But we definitely have a slightly divergent palate, for sure.

What are some of the staples that you make for yourself or for yourself and your husband? What would you cook on a regular weeknight?

I love making like a very crunchy green salad, like a sort of gem-based salad with lots of different vegetables, whatever's seasonal. Recent iterations have had sliced cherry tomatoes and fresh corn cut off the cob and Jimmy Nardello peppers. And then I’ll sometimes do like a pastured chicken breast cut really thinly, a kind of paillard, just covered in herbs. I’ll pan fry that and then slice that and have it on top of the salad. And that's just a perfect meal. You really don't need anything else.

The other thing that I love to do (and we do this at least a couple times a month) is just a veggie taco night where we prepare all kinds of different vegetables and then make corn tortillas. Like long-cooked, slow-roasted carrots—which are so good in tacos! You never see that in restaurants, but they're so meaty, and you can really season them in a way that feels meaty, with like paprika and cumin and different spices, black urfa chile and stuff like that. And then we make guacamole and various salsas and add beautiful, caramelized onions and whatever’s in season, like shaved cabbage salads and fresh coriander (sorry, cilantro; I lived in England and it haunts my lexicon).

What parts of your approach to food do you try to share with people?

One of the things that I try really hard to instill—especially in any social media presence, or even through the writing of the recipes in my book—is that you are your own best guide to how you cook and the necessity of learning how to trust yourself. There are absolutely a few essential lessons to learn, technically, so that you feel more confident, but the idea that there's any real standardization around, like, how much lemon juice to put in something is, I think, this falsehood. I want people to cook more intuitively. And, obviously, I grew up steeped a really rich culinary household, so it's a little bit unfair to me to say that, but at the same time, I really want people to taste things and respond.

Not every carrot tastes identical. Some carrots are going be perfect for a slow-roasted carrot dish and will really caramelize, and some carrot will taste kind of starchy. Not every carrot is the same. So, the idea that a recipe calls for whichever carrots are there doesn’t work. You have to actually taste them and see if they taste right. Smell what you’re working with. Are the spices fresh? Do you need to buy new spices? There are these things that we don't necessarily explore, either out of fear or discomfort in the kitchen, or whatever it is.

We should ask ourselves these questions about where we're getting things and what we actually like and how we want to cook. Taste and adjust. We’re not doing really exacting baking, which is maybe the one time you kind of have to really hew to a recipe. It’s really about what your personal preferences are. I probably like my salad dressing far more acidic than the average person. So, make sure that it tastes balanced to your palate.

Caramelized Carrots with Lemony-Garlicky Yogurt, Pomegranate, and Pepitas

This recipe—which I’m running almost exactly as Fanny wrote it—is the same one that Fanny uses for carrot tacos but turned into a dish that stands on its own, with a lovely yogurt sauce. To use the carrots for tacos, skip the seasoned yogurt (though the pomegranate seeds and pepitas would be nice in the tortilla) and add some guacamole, a few kinds of salsa, and some cilantro and slivered radishes.

Serves 4-6

2 bunches of large carrots (the sweeter the carrot raw, the better it will be cooked)

Olive oil

Sea salt

Black pepper

1 cup of sheep's milk yogurt or labneh

1-2 large cloves garlic, peeled (depending on strength; if it's on the spicier side, use less)

1 teaspoon ground sumac

1 teaspoon Aleppo chile

1 organic lemon

1 organic tangerine (or small orange)

½ cup pomegranate seeds

¼ cup pumpkin (pepita) seeds or almonds

¼ torn herbs for garnish (parsley or cilantro)

Preheat the oven to 350°F.

Cut the greens from the carrots but leave a little nub at the top. Scrub them thoroughly but leave them unpeeled. If they are especially fat, cut them in half lengthwise, through the stem. Toss in olive oil to lightly coat, sprinkle with salt and freshly ground black pepper. Lay in a single layer on a sheet pan and put them in the preheated oven.

Meanwhile, pound the clove of garlic in a mortar and pestle with a pinch of salt until completely pulverized. Add the zest and ½ a tablespoon of the juice of the lemon and allow to sit, macerating, for 5 minutes.

Add a cup of sheep's milk yogurt or labneh to the bowl of the mortar and use a whisk to incorporate it well. Add the zest and a tablespoon of juice from the tangerine. Add the Aleppo chile and sumac and a good glug of olive oil and whisk to mix. Taste and adjust seasoning, using a bit more yogurt or olive oil to balance the flavor or consistency.

Toast the pumpkin seeds in a pan until lightly browned and popping and set aside to cool. (If using almonds, toss in a tiny bit of olive oil and salt and toast on a sheet pan in the oven until lightly brown and fragrant; when cool give them a chunky chop to break them up a bit.)

Carrots will cook at different speeds depending on their size and the season, or how watery or sweet they are, or even how hot the oven is, so cooking time will vary. It could take as few as 45 minutes, or as long as 1 ½ hours to get them to a place where they are tender and yielding and their skin is caramelized, browned and little shriveled, but the texture is still far from mushy. It's important to keep an eye on them, but also be patient. After about 45 minutes, you can turn on the convection function on the oven (if you have it) to get them extra caramelized. The broiler will also work. That said, you definitely do not want to overcook, char, blacken or dehydrate them, so it will require vigilance at this stage (it can take a little trial and error!)

When the carrots are done, remove from the oven and set aside to cool. Spread the seasoned yogurt on the platter using the back of a spoon to give it nice undulating waves. Lay down the carrots with the tops aligned. Sprinkle generously with pomegranate seeds, then zest the remaining half of the tangerine over everything and sprinkle a little juice overtop. Add the seeds or nuts. Toss a handful of herbs on top as a final touch and serve.

NOTE: The carrots and yogurt make a great veggie sandwich filling: just cut a length of un-toasted, fresh baguette, spread on the yogurt and add the carrots and a few leaves of arugula.

Photos courtesy of Fanny Singer

Fascinating work! Luved it . . . .