I hope everyone had a lovely Lunar New Year and Valentine’s! And if you’re in California, I hope you also got to enjoy the (admittedly alarming) unseasonably warm weather we had last week; there’s more about the ramifications of that heat wave on the state’s crops below, in the further reading section.

This week I’m sharing the conversations that I had with Oakland-based celebrity chef Tu David Phu last year. Tu is Vietnamese American, and he cooks what he refers to as “Vietnamese Diaspora Cuisine” influenced by California’s foods and flavors. His beautiful, inventive versions of his family’s foods earned a lot of praise and attention on Bravo’s Top Chef Season 15 and have been featured in a variety of media outlets. Tu is also a community advisor for the Oakland Asian Cultural Center, a James Beard Smart Catch Leader, and an advisor to the Real Food Real Stories project.

When I first started diving into the question of what “California food” means today, Tu became one of my earliest and most generous cheerleaders and connected me to a number of the Bay Area’s most exciting chefs. He also shared his family’s story with me and talked about how his parents’ foods, and their struggles, inform how he cooks. Here are pieces of those conversations, edited and condensed for clarity.

Tu David Phu

My mom’s cooking isn’t traditional Vietnamese. It’s influenced by the places my parents had been before arriving here in Oakland, in particular Thailand, Vietnam, and Minnesota.

When they lived in those places—especially Thailand, in a refugee camp, where they were on the run for their lives—they had to learn how to cook and fend for themselves and feed themselves. And my mom took that with her here to the United States. Coming over to the United States, she lived in mixed communities with all sorts of different people.

Naturally they would gravitate toward other people who spoke Vietnamese. In my youth, my mom moved next door to a woman who was of Korean descent, and she actually spoke Vietnamese, coincidentally. We thought she was Vietnamese for the longest time, until we got to know her a little bit better.

She taught my mom traditional Korean dishes, and then my mom, in turn, cooked them for me to eat. That whole time, up until my adulthood, I thought those dishes were Vietnamese. Isn’t that insane? I just got engaged [in February of 2021], and my fiancé is Korean. So these ideas of where these dishes came from didn’t come fully full-circle until I really dove into food conversations with my fiancé. Isn’t that funny?

For example, Vietnamese folks, across the board, are absolutely obsessed with anchovy fish sauce. And to add to that, in my family (especially on my maternal side), we’ve been making fish sauce since 1895. We’re from the island of Phu Quoc, in Vietnam, which is known as the fish sauce producer of the region. So we’re big anchovy people. One of my favorite dishes growing up, which was Korean (but I thought was Vietnamese), was crispy fried anchovies. These are tiny, tiny anchovies, probably like the size of a needle. You fry them, and I think there’s a slightly sweet cure on them, then you dry them—you have to dry the fish to get them crispy—and you spice them with jalapeño or something (that’s my mom’s way), and you eat it with rice.

My mom cooks different things, influenced by what she learned over the years. She gathers corn silk—you know, the fibers from corn—and she saves them and dries them. You can put it in a stir-fry, you can make a tea out of it, you can put it into soup. When she makes nuoc cham, which is the Vietnamese fish sauce, she uses Sprite. Traditionally that recipe calls for coconut water, so that’s a pivot all of her own. We use it as a table condiment for dipping, to dip your vegetables, your meats, your spring rolls.

My dad was a career-long fishmonger at Pier 45, for a Japanese fish company that’s no longer around. All the Pier 45 wholesale fish people knew him. He was legendary. People don’t stick around as fishmongers as long as my dad did, because that work is so laborious. You work the midnight shift in a refrigerator. It’s a young man’s job, but my dad spent a lot of time there. He was just a monger, on the lower end; he wasn’t like an owner or a boss or anything, he’s just that big Asian guy who’s worked almost every job on the docks.

He learned to cut tuna and stuff, and with that new craft that he’d learned—especially doing tuna for sushi, and that kind of stuff—he started to translate that and bring that home. So we would make things like Vietnamese summer rolls with number one-grade, sushi-grade tuna. We would eat it raw like sushi, but with spring roll wrappers and fish sauce. It’s so amazing! We love it. It’s super California to me.

I have some funny stories: One of funnier ones is that my dad would bring home lobster. These seafood places would keep lobster in their freezer, because it wouldn’t sell or whatever, and my dad would take the leftover frozen lobsters that no one wants to buy. Given my dad’s Southeast Asian background, he loves overcooked meats, especially fish. He would over-steam the crap out of the lobster. I’m talking about a one-hour steam. It was horrible. So, because of that, I really hate lobster. I’m scarred because of the way my dad overcooked the lobster.

It was beneficial for my father to be in the food industry, because that would help get food on the table. He brought home a lot of salmon heads and a lot of salmon belly. And I have to tell you this: the seafood industry is probably one of the most wasteful industries, because they only go for center cuts. At least in the meat industry, all the leftover parts can be ground and made into a hot dog or hamburgers. It’s not the same in seafood. People only want the loins, the flesh. And ninety-eight percent of the fish is edible, including the gills, the bones and whatnot. But it doesn’t get repurposed, it gets wasted. My dad would always take home the bones, the head, the belly. And those are the most prized things in Vietnamese culture because it’s those specific cuts that also have the most gelatin.

So we would make canh chua, which is Vietnamese sour soup. The way we made it was with a base broth of lemongrass and pineapple, sometimes tamarind. We ate a lot of that. You put in the greens of a lotus root—think it’s called elephant ear, something like that—pineapple, firm fresh tomato, beansprouts as a garnish, some other herbs. The way you start off the broth is you start with a “Vietnamese sofrito,” if you will. That’s ginger, shallot, and lemongrass. And you perfume the pot; you get those to a point where they’re brown and crispy. And from there, you build up your fish stock: you add your water, and then you poach your fish in that. While your fish is poaching, you add the vegetables and the tamarind and all that stuff. So it’s a very quick but high-skill sort of thing.

When my dad got his bonuses, and the economics of the family were good, he would bring home—at an employee discount—sushi-grade tuna. And we would have the sushi summer rolls.

We ate a lot of local rock cod growing up. Rock cod is incredibly cheap and very sustainable. We would cook it whole. We slice slits into the filet on each side of the whole fish and then rub it with fresh Thai chile with salt and lemongrass kind of mortared together. It turns into this chile-salt kind of rub. So we’d put that into the slits of the fish and bake it. That same fish, if we didn’t have salmon heads, would also be made into canh chua.

Those were the staple ways we ate fish. You could guarantee that each week we’d have that at least once. And of course there’s always a vegetable. That vegetable would usually be poached in water and served along with the tea that comes with it. It’s not a soup, it’s more like a tea. For example, if we had a melon gourd, my mom would bring it up to a simmer and season it with a bit of salt. It’s not exactly a soup, it’s not exactly a stock. I think if anything it’s more like a tea, because of the way the flavors permeate through that water.

So there’s always a vegetable, whether it’s broccoli, melon gourd, sometimes daikon, sometimes green beans, sometimes cabbage. Often it was cabbage because it was super cheap. So there’s always a vegetable that’s in a tea, if you will; there’s always rice; and there’s always fish. And that’s on a good day. That’s on a really good day.

We did not eat a lot of meat growing up. If anything, we ate a lot of seafood, because my parents were both pescatarians up until they came here. Because being an islander, eating fish was always the cheaper alternative. You didn’t buy it, you always just fished. So, in our household, when we did eat meat, it was more so like my mom would get chicken bones from the butcher, and she would make a simple chicken broth to eat with rice. It was kind of like, I don’t know, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory cabbage soup sort of status. We would get chicken bones from the meat market for free, because back in those days no one bought chicken bones, they were just given away.

In my youth I drank a lot of milk—a lot a lot of milk. Because it was cheap. So that was a big basis of my nutrition. My mom would tell you that I drank a lot of milk even into my teens, because I was always hungry. On those days when there wasn’t food in the house, if my mom wasn’t able to get that on the table, there’s always the guarantee of milk in the fridge. Back in those days, a gallon of milk, like the shittiest milk you could get—we’re talking like Food Max or corner stores—you could get a gallon of milk for like a buck fifty. There would always be a gallon of milk. And I knew that would always be my default.

I think for a lot of years, the food insecurity translated into my manners with and around food. For years, I always ate like there was going to be no more food. I always remembered growing up hungry or going to someone’s house and eating up all their food. And of course I was a healthy kid, but I feel like I was hungry a lot of those times. I think it’s both helped and hurt me; scarred and built me up in like a very twisted and complex way.

Since I started working with food, and cooking with my mom, I’ve gotten to know more about who she is as a person, all the things she’s gone through—especially war. The kitchen was a safe space for us. Outside of cooking, I never learned who my mother was. My parents never talked about their experiences in war; they never talked about their struggles. That all happened over a recipe. And these recipes, in these certain moments of cooking an item or talking about an item, would have memory triggers for them. And it was how I was able to get very, very close to my parents. Food was my saving grace, in terms of giving me opportunity, but it also has brought me closer to my parents.

My relationship with my parents is fairly complex. I think when people talk about cooking with your family and matriarchs, people think that it’s happy and sunshine. To be very transparent, my parents have suffered greatly from their experiences. Often times, I find that I’m dealing with their PTSD. I find that I’m walking on eggshells when figuring out how to further connect with them. To be honest with you, there are great moments and there are very difficult moments. And I say this to be really transparent, because often people talk about the food of different cultures without acknowledging the struggle that comes with it. You might love pho and Vietnamese food, but you don’t acknowledge all the repercussions, all the policy and legislation that really hurt people during the Vietnam war, both American veterans and Vietnamese. So I try to be very conscious and careful about how I’m celebrating things.

When I think about how I’ve taken my parents foods and turned them into my own dishes with high-end presentations, I think about art. My fiancée and I really love art. And I think the reason that I admire artists is that they can look at something and see a beauty in it, and then they can illustrate that for you through their art.

I’m trying to have that sort of understanding around food. I feel that a lot of people would see my mother’s food or my family’s food as not beautiful, but I want to show it in a way that people can see that it is beautiful. It’s less an interpretation or how I express myself; it’s more that I want people to see how I see this type of food—how I interact with it and how I feel about it.

Recipe: THỊT KHO ĐẬU HỦ

(Vietnamese Caramelized Pork with Tofu)

This dish is Tu’s slightly elevated take on a traditional Vietnamese favorite made with pork belly and tofu. In his original recipe, he calls out the specific artisans and purveyors he buys from—including some of my very favorite Northern California food producers—so I’ve included that info here in the ingredient list, the way he does. But don’t be afraid to swap in whatever pork, tofu, eggs, and good fish sauce you can get your hands on! The dish will be delicious either way.

Serves 6

Total Cook Time: ~ 1 hour

Active Cook Time: 45 minutes

Ingredients:

2 tablespoons avocado, sunflower, rice, or canola oil

½ pound Stemple Creek pasture raised pork jowl (or bacon) cut into ¼” cubes

2 pounds Stemple Creek pasture raised pork shoulder

4 oz. Hodo firm tofu, cut into 1” cubes

2 teaspoons minced garlic

1 teaspoon minced ginger

1 ½ cups organic sugar

¼ cup Son Fish artisanal fish sauce

½ teaspoon sesame oil

1 medium yellow onion, sliced

1 tablespoon kosher salt

½ teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

Rice, for serving

Alexandre Farms fried eggs, for serving

4 scallions, sliced, for serving

Pre-heat a large, heavy skillet or dutch oven with oil on medium heat.

Once the oil is shiny, add the cubed pork jowl. Render the pork jowl until it becomes light brown and crispy. Lightly season it with salt and pepper.

Lightly season the pork shoulder with salt and pepper. Spread the pork shoulder chunks across skillet evenly, and brown them on all sides.

Add the sliced onion, minced garlic, minced ginger. Cook until the onions are translucent and caramelized.

Remove the roasted meat and aromatics from skillet, and set them aside to add later.

Put 1 cup of the sugar into the same skillet you used to cook the meat, making sure to cover the bottom of the pan completely; place it over medium heat. As the sugar melts (all sugar crystals should dissolve) add the fish sauce. [Note: Don’t burn the sugar.]

Add the tofu, aromatics, and browned meat back to the pot. Stir gently to combine the fish sauce caramel with other ingredients in skillet.

Add the remaining ½ cup sugar and the sesame oil, salt, and pepper. Lower the heat to a simmer, cover the pot with a lid, and reduce the sauce for about 20 minutes. If the pork hasn’t caramelized by the end of 20 minutes, raise the heat and sauté the mixture while sauce further reduces.

Serve the dish over rice, topped with the fried egg and garnished with the scallion.

More California Stories to Read, Watch, and Listen To

If you want a peek into Tu David Phu’s life with his parents, and how they cook together, check out the short documentary he produced, Bloodline.

Last week, KPIX (the Bay Area CBS affiliate) did a good job of reminding us that while many people probably enjoyed the state’s unseasonably warm weather, these hot spells can be terrible for farmers.

This week, KQED has a great piece about how Eat the Culture, a collection of black food bloggers, is exploring Afrofuturism through food. Writer Luke Tsai spoke with Bay Area food blogger Stefani Renée of Savor and Sage about Eat the Culture’s goals and how participating bloggers are exploring this topic; Renée’s contribution, a Coconut-Lime Cornmeal Tres Leches Cake, looks phenomenal.

Last but not least for this week, the Santa Barbara Independent reported that the Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians has decided to close Kitá Wines, which has been home to noted winemaker Tara Gomez, a Chumash descendant. Sad news for the local wine community.

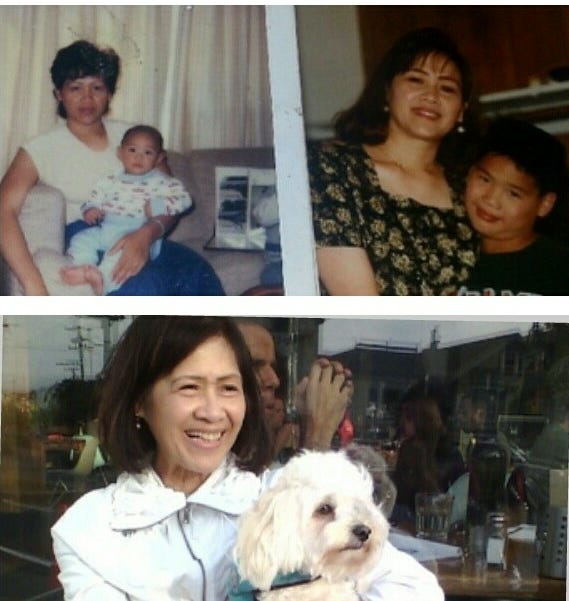

Photos: Tuna Summer Roll by @spencerbrownphoto; all others courtesy Tu David Phu