Hello, Cooks and Readers - Today’s newsletter marks the start of a new format I’m going to try out: separating interviews and recipes. Each interview will still come with a recipe (or two) from that cook, but that piece will arrive later in the week, as a separate email/post. I’m hoping that this will make the recipes easier to navigate and use (both in your inbox and on the Substack app and website) and it will have the added benefit of making each missive shorter and easier to read. I’ll also be re-sending some old recipes as I separate them out from their original interviews, so if you haven’t had a chance to dig through the archives, you’re in for a treat!

In the meantime, I have the glorious job of introducing today’s subject: physics professor (and artist) Hilary Jacks. Hilary first moved to California about a decade ago, to go to graduate school in Berkeley, and she is now a professor at Cal Poly. We talked about how growing up in Miami shaped her understanding of food and how cooking can provide a sense of community and ritual. (Our conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.)

In a couple days, I’ll share the recipe that Hilary sent me after we talked: a simple-but-hearty no-cook salad full of beans, greens, and fish that was a huge hit with my extended family when I made it a few weeks ago. It’s a great way to use up leftover fish, so if you’re making salmon or trout—or any fish—for dinner this week, save a filet or two!

Hilary Jacks

Growing up, things were relatively boring, food wise, at home.

I was born and raised in Miami. My mom is English and Irish. She ended up in Florida because they were from New York—they were Irish and English immigrants—and my grandmother left my grandfather in the late 60s, which was thing you didn't do then in a strong Irish Catholic community. And, so, my grandmother got the kids in the car and went to her mom's place in Miami. And that's still the house my mom lives in today. I think that house was purchased in 1929; it's been with us for a while.

My dad is Polish and Irish but heavy on the Polish. His parents were from Michigan and they wanted to retire in the Keys. They were dentists, and they had enough money to buy a house down there. My dad eventually ended up at the University of Miami and kind of settled there.

At my mom’s house, she didn't really like to cook much. My grandmother lived with us, but I think she cooked way too much as a mother of five in the ‘50s and ‘60s and was just done with being in the kitchen, almost from an ideological standpoint. By the time I was 12, I feel like I was kind of cooking for me and my sister. But we were doing pasta. It was pretty straightforward.

At my dad's house, my dad was always the one who cooked, even with my stepmom present. My stepmom's Italian, so we had some Italian immigrant-New York-style recipes and stuff. She does really great peppers and eggs. Last weekend I just made her meatballs again. But mostly it was my dad cooking.

I think the big influence at home for me was my dad and his garden. We were just in that garden all the time. There are pictures of me on his back as an infant, and he's there with a shovel. We were in the garden every day, just tending to things and always really involved, as kids. And at every meal, I would say, he found a way to include something from the garden or from one of the citrus trees or the mango trees. Whenever they were in season, there was always mango on the table.

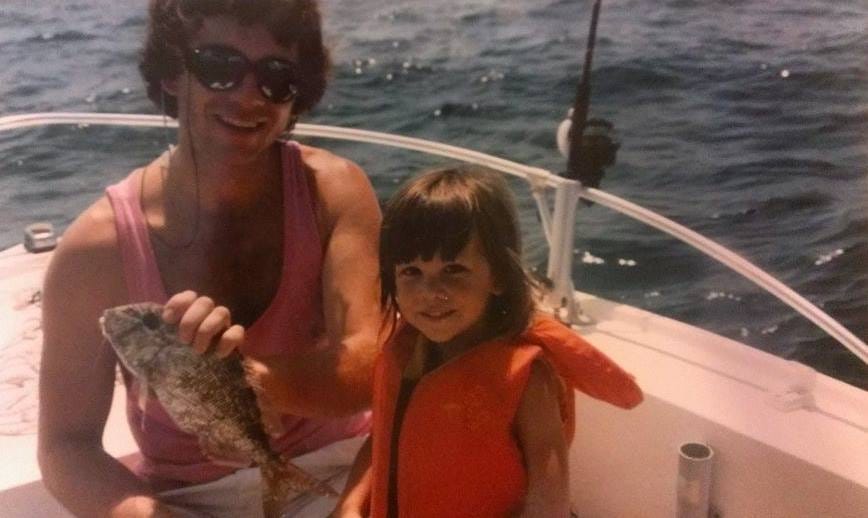

My grandparents lived in the Keys, and we would go down there and go fishing, and we ate what we caught. Fishing is—I don't know, I was thinking about it—it's different than farming, right? It's kind of more akin to foraging in a way. There was a tradition and a ritual about it that really appealed to me. I remember getting back home and helping my grandfather clean the fish and then going into the kitchen with my grandmother and seeing all the different ways she would prepare them. I think that was big for me, growing up.

I think a huge part of my food history is outside of the home and all of the different types of food that Miami had to offer. In high school, we didn't have a cafeteria. I went to an arts high school. It was in the middle of downtown Miami in some old business building that we kind of took over, and there was no cafeteria, so we had to be let out for lunch. There was a Jewish deli, there was a Jamaican place (which we went to constantly), Cuban food like crazy, Nicaraguan food. I was fortunate to be in a very multicultural city.

I think my interested in cooking really started in earnest when I would go to my friends’ houses. I had a friend who was Pakistani and Cuban, for example, and I would love to go over when her dad, who was Pakistani, would have “Cooking Day.” He would cook, and we would help with that, and I would learn. Or visiting my Cuban friends, helping prepare for New Year's Eve, for example. You're tying up a pig and hosing it down and digging a hole in the backyard and rigging up, like, a lawnmower motor to make a spit.

There was something about this coming together and learning of people's traditions that I really, really loved. I adore Passover, probably because I was just like, Oh, can I please not just come to your Seder but also help you to prepare food? Oftentimes I would be more interested than my friends, who were like, Oh, we've done this. There were just all of these really amazing cooking opportunities that I had with friends growing up that I really liked to be involved in.

Our big family cooking thing, on my dad's side, because of the Polish influence, was making pierogi. And that we probably did that about twice a year—Christmas and Easter usually. That was like a day-long family gathering.

I started cooking for myself in college. A lot of it was bad—but not boring. I was in art school, and I was very experimental. I would try to replicate things. Like, I had a professor who was Lebanese, and we went to her house, and there was a dish there that I really liked, so I asked her for the recipe. And I totally botched it. It was terrible. But I ate it anyway because I was poor and had to eat what I made.

I was always experimenting with different recipes. I think I also started kind of getting back to some of my family stuff at that point, especially my stepmom’s Italian recipes. I was calling them and saying, “Okay, this thing that I've eaten a hundred times, how did we do that again, exactly?”

I ended up in California by applying to grad schools here. How I decided to go to graduate school for physics is a longer story, but once I knew I wanted to go to grad school in physics, I had already lived in the Northeast (when I went to art school), and I hated it a lot. I didn't want to live there ever again. So, to the chagrin of my undergraduate mentors, I did not apply to Harvard, MIT, Princeton, all that. I felt like I wasn't going to sacrifice my physics education by choosing a graduate program somewhere in California. I had family out here—my oldest aunt, Louise, and her three kids and their kids—and there was the exotic, liberal allure of California that I felt like I really identified with, even though I didn't live here yet.

Moving to Berkeley was huge, food-wise. There's nothing like living in Berkeley, for me. I don't even have to tell you about Berkeley Bowl— just the experience of going in there and having so many options and having to be like, Okay, there's only seven days a week. So out of all of these things I want to cook and try, how do I fit that in? Or seeing something that I'd never even heard of before and looking it up and trying to find a recipe that included it so I could learn about it.

Being in California also introduced me to other foods, like Mexican food. And I know that's a broad category that's so rich and multifaceted. But I just really had not experienced much Mexican food at all. So that was the first big kind of revelation. And more Asian food. Two of my favorite restaurants in Miami were a Thai restaurant and a Vietnamese restaurant, but there wasn’t Chinese or Japanese.

I was living with this woman on the north side named Suzanne. Suzanne's job was grocery shopping for other people. But, you know, in Berkeley, you don't go to one grocery store for your stuff. If you're really a foodie, you want to go to the seafood market on this street, and the farmer's market over here for this particular thing. And that's what she did. She ran around every day with all these very picky, discerning people's grocery lists, and just bought food.

I don't know if I should say this (Suzanne, if you hear this, forgive me)‚ but she definitely skimmed some. So, I was exposed to more things. We had stuff in the fridge, and it was just constantly cycling and constantly new. It was amazing. And she would cook! Her mac and cheese was, like, I don't know, a hundred-dollar mac and cheese. She'd get the best of seven types of cheeses, and it was just incredible. I didn't have a ton of time in grad school to cook, but, wow, the stuff that came in and out of that house.

When I moved out of Suzanne’s, I kind of started to build up a repertoire of things to cook. I was very, very interested in determining, like, Okay, this is a go-to for me or This is a thing I could do on this special occasion.

My best friend and his boyfriend got me really into Yotam Ottolenghi, so I remember there was a period of time when I was going through his recipe books and just kind of checking recipes off just to experience them and to learn different ways of cooking things. I was making a lot of farm-to-table, Berkeley-inspired food at that point. A lot of CSA-box recipes. I remember making a lot of veggie stuff because it was inexpensive enough for me. There was this lentil soup that I worked on and worked on, week after week, even in the summer when it was hot as blazes in the apartment. The recipe was from a farmer's market-type pamphlet or something that I found. There’s cumin and lemon and cilantro and carrots. It was very basic. But it was like, Okay, can I make my own broth? Let's do that. Or, what happens if I shred the carrots instead? Pretty different in terms of the sugar content. Or, what about using Meyers instead of the other lemons?

I focused on maybe 10 different recipes at the time, from kind of all over the place. I wanted to make them mine and make them things that I could do without looking at the recipe. Other recipes on that list include stepmom's meatballs, which I've changed. And there’s an Ottolenghi rice dish with olives and pomegranates that’s baked. A good roast chicken—it sounds trivial, but chicken with a good green goddess sauce, that was definitely a go-to. Cuban dishes, of course, like a picadillo, because there's no Cuban food out here to speak of, and I missed that so much. In graduate school, we had a postdoc who was Catalonian, and he taught me how to make a Spanish tortilla. And there was an avgolemono—a Greek lemon, rice, and chicken stew—that I would work on.

I think a big motivator for me was that I was getting ready to have a family at that point. I felt like, in my house growing up, there were a few go-tos, but it wasn't really an interesting food upbringing. And that's something that I wanted to give my kid. So, I was like, Okay, I'm going to be a busy mom, and I want to expose my kid to a lot of different flavors. What are these things that I'm going to build? It really it was like it was a conscious building effort.

Being an academic in STEM, there's not a good time to have a kid, especially as a woman. Physics, out of all of the STEM fields, we do the worst for inclusion of women. I always knew I wanted to have a kid—always, always—so starting in undergrad, whenever there was a female physicist that had a kid, I would try to make an effort to pull them aside. I remember even being at a conference and being like, “How did you decide to have a kid? When is good? Tell me, you had one, when is good?” And the consensus (based on nothing—not like any kind of scientific sampling methods) was that grad school is actually best, because it's demanding but you are actually most flexible in grad school.

Covid was huge for me, cooking wise, as it was for a lot of people. I was in a pod where it was the worst version of meat-and-potatoes cooking. I was like, We can't keep doing this. A big motivator for me at that point, too, was not just introducing my kid to these foods, because he was in our pod, too, but that the kids in the pod wouldn't eat anything. And they were like 10 and 12. I was like, This is outrageous. We need to do better. I'm going to do better for everybody here, whether you like it or not. We're eating different. We can't keep doing this. So, I was doing two or three new recipes a week. And a lot of that was from, again, Ottolenghi cookbooks, magazines, or I would go online and find something that I thought would be fun.

The adults were all happy to eat what I made. They were just not cooks. And it was really nice for me, because, I think, it was the first time I really had a community to cook for. It showed me how much I really like cooking for people.

At first there was a lot of complaining from the kids. And at some point, I said—just calmly at the dinner table—"If I hear one more complaint, I'm never cooking in this house again.” And that was it. Apparently, they enjoyed it more than they let on, because that was years ago and there have been no complaints, and these kids are now my step-kids. Now if somebody else is cooking, they're not thrilled. They're like, “We want Hilary to cook.”

Post-COVID has been hard, because I don't get to cook as much as I did, so I really had to pare it back to one or two fairly involved meals during the week, then leave the rest up to my partner, or get takeout, just because work has been—work. And teaching post-COVID is not great.

I also do things that my son can make, or at least help me make. We still do the pasta and meatballs, and he's helping me with the meatballs. I think he can do a reasonable omelet at this point; we watch the egg and wait until the right time, and he needs help doing the flip. And now my stepdaughter is like, “I love to cook, I want to learn how to cook.” So, we’ll cook together.

I still do lots of picadillo. And a Cobb salad, from time to time, because it’s a good way to clean out the fridge. And the chicken. I guess, now that I'm thinking about it, a lot of the things that I had worked to build in grad school are things that I do now.

I think a thread for me is that cooking is a family thing. It’s not something that I learned from my family, but it’s something that was really important to me in making a family. Looking at my life and how little the focus was on cooking when I was growing up, it's kind of odd that I ended up with this kind of focus. But for me, just learning different traditions and ways of doing things, and incorporating what works for me, is a central part of building a household. Without that, I don't know how I would do a household. And it was clear to me even before I had a kid that I really wanted that. I think it's because I went to friends’ houses and saw it.

I like adults appreciating my cooking. (I love when my mother-in-law is impressed. Who doesn't love that?) But impressing a kid, or giving them something that makes them feel that comfort, something they can rely on, that's huge. I guess I've made the time over the years to make that happen. And I really liked seeing all the different ways that that could happen. Growing up, I didn’t really feel a strong sense of that with my family. But maybe that made me more open to things—because I had to go out and find it.

From the Archives

The recent heat wave marked the start of really good tomato season in the Bay Area, so I’ve been making this stone fruit and tomato salad pretty much every day. It’s a perfect summer breakfast—or lunch or snack or dessert.

Note: If you have thought or feedback about this new format, please leave a note and let me know!

Photos: Courtesy Hilary Jacks (4), Georgia Freedman (2)

Delightful Hilary. You will do well in this endeavor

Aloha

Eleanor