Summer feels like it’s really in full swing in the Bay Area now—even if the school calendar (and the way-too-early Halloween and pumpkin-spice everything) seems to want us to believe it’s already fall. Some of my favorite produce was late this year, so I’ll be spending the next few days eating O’Henry peaches and Tomatero tomatoes every chance I get. Maybe the hard green fruit on my fig tree will even start to ripen? (I can always hope!)

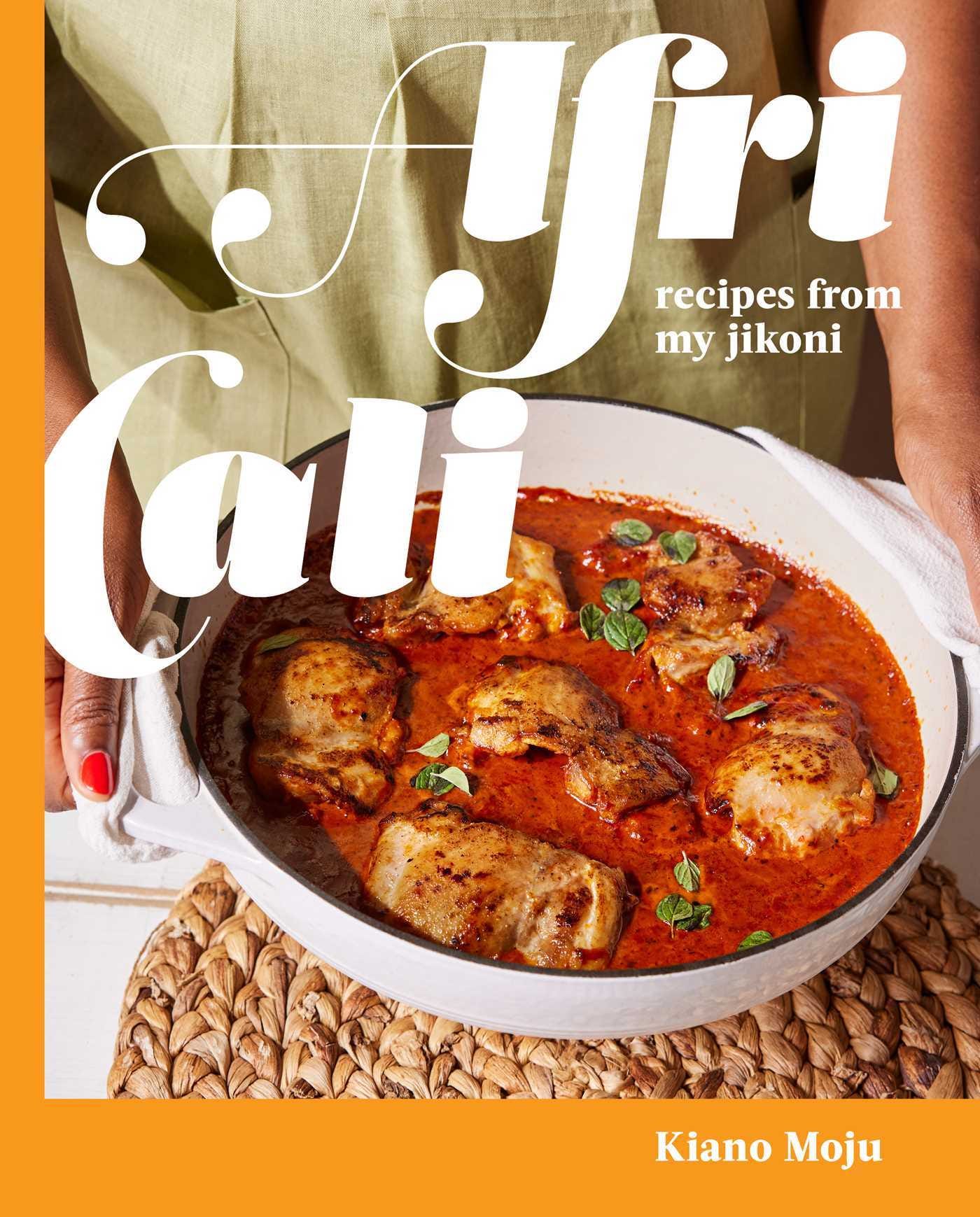

This week I am thrilled to be able to share an interview with Kiano Moju, a Kenyan/Nigerian American cooking video producer (formerly of BuzzFeed’s food video vertical, Tasty) and author of the cookbook AfriCali: Recipes From My Jikoni, which was released last week. Kiano and I talked earlier this month, and she shared stories about growing up in the Bay Area, visiting her grandparents in Kenya, and becoming obsessed with food as a kid. She also shared her zucchini-feta bhajias recipe from the book, and I’ll send that out in next week’s newsletter. Here’s what Kiano told me, edited and condensed for length:

Kiano Moju

My parents are from two different countries. My mom's from Kenya, my dad's from Nigeria. They both came here for school. My dad came for grad school at UC Berkeley, and my mom, she came—mind you, they did not meet when they first came—but she came for high school. She came on an exchange program up in Marin County.

They met a house party, when they were both grown, that was being thrown at my dad's place. I think at this time there was a really great pan-continental community of young Africans living in the East Bay area. They all hung out together, partied together. So, my mom's friends knew my dad and invited her to this house party.

I grew up in the East Bay. I was born in Oakland; my mom was living in Marin, and Kaiser didn’t have a maternity ward in Marin, so I was born in Oakland. And I moved to Oakland in the fourth grade. But I've lived all over the East Bay. We lived in Hilltop, and I went to elementary school in Berkeley while living in Oakland. The East Bay is my home.

I think I didn't realize how lucky I was to grow up eating everything. My mom worked, so her cooking would mostly be nights and weekends. For breakfast—and my memories really are from Middle School on, or late elementary—I was just eating American stuff. I would negotiate Eggo waffles, and I was always running late, so it was an Eggo waffle wrapped in a paper towel with blackberry jam. And I would snack on that on my way to school. I went to this really small schoolhouse in Berkeley, called the academy (like K through eights was 100 kids), and I think we had school lunch every other day, so it'd be pizza and then burritos. (Burrito day was always the best.)

On days where we were supposed to bring lunch, I (confessionally) sometimes “forgot” to bring my lunch because I didn't want whatever was in it in the first place, and I’d call my mom and be like, “I have no food.” So, she’d grab me a burger from Smokehouse, which I think is still there, or a tuna melt from Ozzy's soda fountain, which is something different now. That tuna melt was, like, the best thing under the sun for me.

And then evenings and weekends is when my mom would do the cooking. She would make simple Kenyan dishes like wet fry, which is sauteed meat with tomatoes and onions. It's kind of like a stir fry but the tomatoes make it wet, so we call it wet fry. And we eat that with maybe some sauteed greens. She loved broccoli. (I, as an adult, have never purchased broccoli a day in my life. Tells you how I feel about it.)

On the weekend, she would really go for those more classic Kenyan dishes that take more time, like chapati, ugali. She has a couple brothers that live in the Bay too, so on a birthday or something, we would find some goat or lamb and barbecue that. And then my dad, where he's from in Nigeria is the Nigerian delta, which has “water food,” which is opposite to my mom's cattle ranching family. So, he would make a lot of—in Nigerian they call them soups, but for an American we would interpret them as stews, just based on the amount of liquid and how thick they are—typically with seafood. So, Nigerian seafood stews. They’re really good. Both my parents are great cooks but cooks of necessity.

I would bother my mom about cooking from when I was really little, like from toddler age. I'd be in the kitchen with her, and if it was a weekend, and she was making chapati, she would hand me a piece of dough. And I was very insistent that everything mom's dough did, my dough had to do. So, hers got rolled out, mine needed to get rolled out. Hers went in the pan, mine needed to go in the pan. I think there's a lot of kids who, when you bring them into the kitchen, they want to hang out but they lose the interest really fast. And I never lost the interest.

So, by the time I was, like, six, and she bought me an Easy Bake Oven for Christmas, she regretted it, because I truly believed I was a pastry chef and would make dessert for my family and force-feed it to them. At that point, she was like, “Okay, you want to learn how to cook. You want to feed us. Let's have you learn how.” So, there was this kids cooking camp at some lady’s house in the Berkeley hills, and she enrolled me in that cooking camp. And I think from then, throughout my childhood, I was taking cooking classes. By age 11, I had enough experience where my mom was like, “Okay, you can cook breakfast.”

If my mom didn't cook, we’d pick up takeout. So dining out was a big part of my childhood. And that, paired with me getting really interested in cooking, led a lot of questions. I was very inquisitive. And I think people are pretty open to teaching kids. So even dining out, I would have questions for the restaurant, like, “What is this? How do you make this?”

I am almost envious of those kids you see in like MasterChef Junior who are like 10 years old and can make better plates than most adults can. I was not that kid. I had the passion, I had the commitment and the focus, but much later in life, my family told me the skills came with time.

I went to London my junior year of college, and there's so many street food markets for lunch. They’re really cheap, or at least they were at that time. It was like five pounds for a lunch deal. And the thing about those markets is that you also get to watch people cook. And I just came in there asking everyone everything: “What's this? What's that? What are you doing there?” And maybe I never wanted to recreate it, but I wanted to try to figure out what is one nice takeaway that I can learn from these people and incorporate into my own cooking, just to make it more interesting, exciting, or different.

I feel like that has always been the way I've looked at food and travel. I spent my summers in Kenya, every other summer, since I was a kid, and it was the same inquisition. I just, honestly, bothered people. And they were very nice to answer me back. I wanted to figure out what was going on, and then once I got in the kitchen, to try to apply my little learnings. That practice—inquire, apply, inquire, apply—is really how my home cooking was shaped.

For me, what makes California’s food unique is two things: One is agriculture—the most obvious one. It's the thing that I think any cook in California will always talk about, because if you live anywhere else, you really realize how lucky we are having amazing produce, really anytime of the year. It's really perspective of not seeing vegetables as like a throwaway or of “We have to” versus “We get to.” We get to use these fantastic things. If you don't have good produce, I think veggies feel like a box you have to tick in your diet.

And the second is really the cultures we have here on the West Coast. I grew up eating such a mix of things. I grew up eating, of course, so much American food but also going to Vietnamese to pick up clay pot and going to my favorite Ethiopian-Eritrean spot, Asmara. My mom is such an open eater, so I've never known a life without trying everything. And I really grew up with great enthusiasm for every type of food. So I have these two fantastic cuisines of my heritage that I get a tap into, but I still have very strong flavor memories of all these other global cuisines that I grew up eating around the East Bay. I didn't have to venture out much further than like Oakland and Berkeley. Between those two cities I got to sample so much of the globe that really made me excited about food and the possibilities of what you can do with ingredients.

My first job in food media was as a video producer for the Buzzfeed food channel Tasty, and the job wasn't just to make videos, we also had to write the recipes for the videos we were making. And making recipes for a brand—especially an established brand—is pretty easy. You just look at what is done well, what audiences like. There's so much data. But I was also figuring out, Okay, this recipe is for the company, but what does that look like for me? What is Kiano’s food? And trying to define my cooking and put rhetoric behind it is how the AfriCali idea first began.

I think at the time we were seeing a lot of folks take on this “third culture” identity. They're like, “I'm Indian American, and so my food is influenced by both.” You see it all the time in these food conversations. So, I'm like, What is mine? I'm from the Bay Area, but my parents are from two different countries. How do I put that into words? And, so, for me, AfriCali started not as a book idea but as a way for me to define my lens on cuisine with the complication of, These two countries tripping me up. At first I thought it'd be so much easier if I had parents from just one country.

Once I figured out the rhetoric to define it, what this book ended up being was an exercise of defining the food I've made based on my heritage and my experiences. Because I wasn't seeing a clear box for it to go into. I've lived it, but how do I explain it and showcase it?

Of all the recipes in the book, one of the biggest staples in my kitchen is the green curry with plantains. I make it all the time. Growing up eating in the Bay Area, I ate a lot more Vietnamese food, but in LA the Thai food is amazing. I've been living in LA since 2013 (with the exception of when I popped out for grad school), and I learned how to make Thai green curry from my favorite Thai restaurant here. And once I learned, it I was like, Oh, we are making this all the time.

A lot of the Thai curries I've had, and the ones I've enjoyed the most, usually have a little bit of squash or something in it. But I can count the number of times I've had squash in my kitchen on one hand. One thing I really feel about home cooking is that just because you've had a dish a certain way in the world doesn’t mean you need to force yourself to replicate it like that in your home kitchen. I'm like, I don't buy this ingredient. I don't enjoy it very much. So why would I use it if I'm cooking for myself?

Plantain have been a staple for my whole life. I love them. And for whatever reason, it's really hard to find ripe ones in my neighborhood. They're usually a bit green, and I usually get impatient. When I was making this curry, which I normally do, I was looking at these plantains, and I'm like, You know, they're probably more or less similar in sweetness to how those pumpkin and squashes normally are. So, will this work? And it was fantastic.

Another one that I do is the Swahili chicken biryani is easy when we’ve got people over and I need something that could feed us all—we're pretty social in our households, we always have people over. My worst nightmare is to feed people and they are still hungry. So I'm like, How do I make a big pot of something that's still pretty? And it's so simple. “Biryani” in the Swahili coast of East Africa—which is Kenya and Tanzania, mostly—differs from Indian biryani. Where in Indian biryani they'll mix together the rice and the gravy, on the coast of Kenya, it's served as a layer of rice and then it's very saucy, like, it's incredibly saucy, which I love. And then you top it with crispy shallots and some fresh chilies. It plates really beautifully. And you just marinate some meat and then let it simmer on the pot until you're ready to serve. So, as a host, it’s really great dish to prep ahead before your guests come. It’s kind of two-for-one: easy for me, beautiful for them. I make this at least once a month.

And then there's a weeknight vegetable, my grandma's cabbage—in the book it’s called Koko's Cabbage—that I make all the time. It’s a very classic Kenyan way of cooking cabbage. You finely chop the cabbage with some carrots, and she has a really clever tip of salting the cabbage before you cook it, because cabbage is so voluminous. Her thing is, How do you salt something evenly in the pot when you can't reach it all? So, she salts in the bowl and massages it, and that also helps to reduce the volume before it goes in the pot—and it's evenly seasoned. My grandma's definitely, without rival, the best cook in our family. I tried to borrow as many of her tips for the book as I could.

One really Californian fusion dish in the book is the short ribs and stew. It might not even be just Californian—I think Americans just love short ribs—but I know you’ll find short ribs on menus top-to-tail in this state. A lot of people still prefer to prepare that classic French style, braised in red wine, but mine is in a spicy, very vegetable-forward stew. Nigerian stew is fully comprised of produce. It like tomato sauce, but it's made with red peppers, tomatoes, and habanero, and the short ribs braise in that. So, it's very thick. I think one thing that we do really well in California is we use vegetables in all parts of our cuisine, not just as a side dish. And this really highlights a neat cut that we're loving at the moment, but it's in this very veggie-forward base.

The zucchini and feta bhajias is another good one. Bhajias in Kenya are typically thinly sliced potatoes dipped in a spiced, herby chickpea batter and then deep fried. It's almost like a round chip but coated. So for this I’m using fresh zucchini, so it feels like a lot lighter, instead of deep-fried, battered potatoes. It’s zucchini, a lot of fresh herbs, feta, and then mixing that in with the chickpea batter. So, it's like a fritter, still, but it's really, really light. And they're just lightly pan fried.

I think the biggest thing about the book is that I was very intentional about curating recipes that are accessible—not in a way of, Oh, this is not scary, but in that you can go to whatever grocery store is around you and find almost everything you need—though maybe there’s one thing or two you can pop on Amazon and buy. I really wanted to introduce people to the flavors that are within Africa, especially the ones from my heritage, while knowing that geographically it is so far, especially since California is at the far side of the country. But you actually don't need to go any farther than your normal grocery store to get these flavors into onto your table. That was a really big part of how I curated these dishes. I wanted it to very intentionally be like can you just pop over to whatever store is near you, get some things, and try out a dish like Coco's Cabbage that is such a typical Kenyan meal.

Photos: Kristin Teig, courtesy of Simon Element

Best interview yet!! Loved it!

Great interview ! Thank you!