For the first week of 2022, we’re embracing our resolution to cook at home more with a super simple, utterly delicious recipe for one-pot pasta with greens. This is the kind of meal you can make on a busy weeknight, when you only have a few minutes to make dinner or you just can’t muster the energy to cook something elaborate. It’s also delicious; once you’ve tried it, you’ll happily make it over and over again all year long.

This recipe comes from the always wonderful Kate Leahy, a San Francisco-based cookbook author. Kate’s family first came to California from Ireland in the 1800s, and Kate was raised here for most of her childhood. After cooking in some of the Bay Area’s most notable restaurants, Kate became a food writer, and she is the co-author of a number of notable cookbooks, including A16 Food + Wine, Burma Superstar, and Lavash: The Bread That Launched 1000 Meals. Last year, Kate published her first solo book, Wine Style.

Toward the end of last year, Kate and I got on the phone to talk about how she became a cookbook author and how her upbringing and time as a chef informs her home cooking. Here is our conversation, condensed and edited; the recipe follows. (One note before we dive in: Kate’s voice is always full of laughter and delight. If you want to really hear her words properly, keep that in mind as you read.)

Kate Leahy

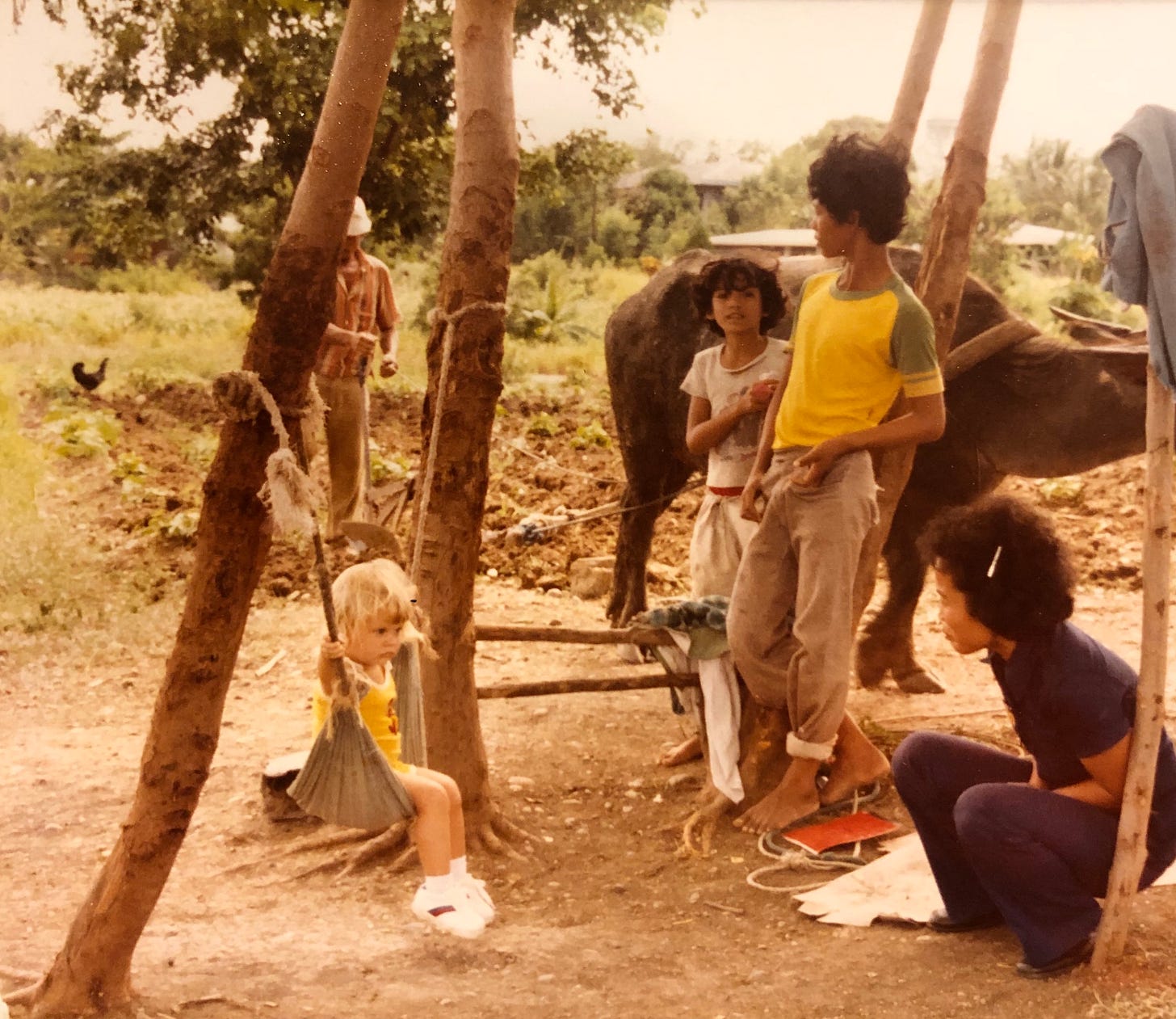

I grew up in Northern California, but I spent my earliest years of childhood in the Philippines, in the southern island of Mindanao. When I was there (when I was a toddler), I was eating sticky rice and fish for breakfast and all these kinds of sweet and savory foods together. I would be found in the pantry with my hand in a jar of something I shouldn't be eating. Coconut sticky rice is my weakness.

My dad used to work for Dole, and he worked on the banana side of the business. Dole had a network of family-owned farms in Mindanao that they would buy the bananas from. It was a kind of co-op, in a way. It was a pretty rural place at that point; where I grew up, we were surrounded by just bananas. I think a lot of that part of the country has been developed now. I haven't been back—someday I will.

But back in the States, you get to school, and you realize like the kids just don't eat the foods that you do. And it was kind of weird. I even started kindergarten with a Tagalog accent. So I'm a white kid, and I do eat, you know, like, “white” food, but people had a lot of processed foods that I didn’t know anything about. I was always thinking about food. I was the kid who, at the bus stop, would interview the neighbor: “So what are you making for dinner?”

When I started cooking, I first got into baking. That happened back to elementary school, because I wanted treats around, and my mom wasn't big on baking. So, if I wanted chocolate chip cookies, she would always have the ingredients, and I could just make them. My mom cooked, and I would make sure there was treats around.

One of my good friends in high school, her dad was really into baking and baking with sourdough. He gave me some of his starter, and I ended up bringing it to college, and I would feed the starter twice a day. My sophomore year, with my poor roommates sleeping upstairs, I would be pounding the sourdough on the counter, making all this noise, and baking sourdough. I baked a lot of bread in college—probably because I wanted to eat it. I used Nancy Silverton’s Breads from the La Brea Bakery as sort of my textbook on how to how to make sourdough at home.

I went to UC Davis, and I was studying history and studio art, but there was something about food that I just really wanted to find a way to do something with. And at the time I thought, Well, maybe that means I get a PhD in history, and I study food and history.

I graduated in 2000. That was around the year where Kitchen Confidential came out and it's also the year, I think, that The Making of a Chef came out, the one where Michael Ruhlman goes to the CIA and learns to cook. And I'm reading these books as a senior in college, and I'm thinking, How can I write about food if I don't actually know enough about how to cook it? I know how to cook student-level stuff, but I want to really know how to cook. And so that took me on a path of learning how to cook in professional kitchens and bakeries that I later tied back to writing about food.

The thing is, I felt like I needed to learn how to cook from professionals, but now I'm learning how much I discounted the amazing ways that home cooks cook. Especially in California. I mean, some of the books my mom always relied on were those Junior League of Palo Alto books, volume one and volume two. And looking back at those, there have some really smart and simple recipes. They’re not long, but you get this great fresh flavor. And those books came out, I think, in the early seventies, and they’re using a lot of fresh produce. They’re using watercress; they’re using ingredients that you just won't see for a while in the rest of the US or in food media.

In California back then, I think we just knew what radicchio was before anyone else. We were used to eating fresh produce because it was close to us. My relatives in Chicago were always amazed by how many salads people in California ate. They didn’t eat salads as much in Chicago, especially in the 80s and early 90s, because the lettuce wasn't that great.

Growing up, we always had home cooking. It wasn't anything fancy, it was just that my mom had to get something on the table. I think we went to restaurants once or twice a year. It wasn't a thing we did. Me and my brother and sister, if we were lucky, we’d go to Round Table Pizza with my dad. But mostly, every meal was at home.

My mom grew up in Mexico City, so we had black beans a lot. My parents would always have chipotle; they'd take a jar of chipotle out, put it on the table, and have that anytime we had, say, tri-tip, or tacos of some sort. Chipotle was definitely a typical condiment. As a kid, it was too spicy; buy then you learn how to love it. We also ate “normal” things—like I said, we'd have our Round Table Pizza instances, and I know that there would be fish sticks when my parents had a babysitter for us—and our food was pretty simple stuff, but most of it was home cooked.

Now when I cook for myself, I feel that the books I've worked on, they linger but not in a front-of-mind kind of way. I don’t often go back to books I've worked on as a co-author and recreate that recipe exactly the way it's written. I usually kind of think, Oh, I remember that when we were working on that book, that this was a technique we used over and over again, and I just run with that.

I have a rotation of certain things. I probably cook more Italian-Southern Italian-California Italian than anything else. I always have a rind of Parmesan in my fridge, even if I might not have any other cheese. I always have capers. I always have some sort of anchovies. Right now, I have, for some reason, two jars of Calabrian chiles in the fridge.

On those days where you're sort of spent and can't think of what you want to make, and you just don't have it in you that day, I'll just resort to throwing together a pasta. I've got some broccolini. The broccolini is going to go into the pot when the pasta is about four minutes out, and then I cook it all together. I’m going to drain it, sweat some garlic, add some chili, add some reserved pasta water, mix everything together—and that's dinner. I know I can put it together fast, and if it needs to be heartier, I can fry an egg and put it on top. Those are kind of knee-jerk recipes that I just make. And if it's not broccolini, maybe it's roasted cauliflower, and I just crank the oven up, throw it in with some capers, and then use that on the pasta—or not have pasta at all and have it with some beans and toast.

At this time of year, I like to do a nice hearty stew, like a beef stew with canned tomatoes. I just braise it with some red wine and some garlic and a little bit of carrot—just really, really simple. And that can be stew one night, it can be a pasta sauce the next night, it could be Sloppy Joe's another night.

This Italian style came definitely came from working at A16 [an award-winning Italian restaurant in San Francisco]. I worked there as a line cook in 2004, the year I had it opened. It was the restaurant to be at in San Francisco. It's crazy. There was so much energy, so many people coming in from all over the world who just wanted to check out this restaurant.

And the food was very simple, but that was when I realized the power of something as simple as, like, fresh marjoram hitting a pan of warm olive oil with a smashed clove of garlic. And then you ladle in nice, locally grown and recently cooked dried cannellini beans. And you get this creamy, rich side dish. I just couldn't get enough of it.

It’s the little things—the order you put things in the pan to extract that flavor, not to skimp on the olive oil, to use the bean water for extra creaminess—those kinds of things really stuck with me.

Recipe: Pasta and Broccoli Rabe with Garlic, Chile, Parmesan, and Breadcrumbs

This recipe is traditionally made with orecchiette, but it could also be great with something like fusilli—it really doesn’t matter, as long as it’s a short type of pasta. You can also use either broccolini or just the florets of regular broccoli in place of the broccoli rabe. (Here, I’ve used the top halves of the broccoli rabe—the leaves and florets—and cut them in half widthwise, so they’re short enough to eat easily with the pasta.) The key, according to Kate, is to make sure you have nice salty water to boil the pasta and greens in; for about five cups of water you want about a teaspoon of salt. As she pointed out when she gave me the recipe, when you don’t have many ingredients, everything matters, even the salt.

Serves 4

Prep Time: 5 minutes, plus time for water to boil

Active Cook Time: about 25 minutes

Ingredients:

1 tablespoon kosher salt

1 lb short pasta

1 lb broccoli rabe (about 1 large bunch), bottom halves discarded, tops cut in half widthwise

2 – 3 tablespoons olive oil

3 cloves garlic, peeled and smashed

2 large pinches chile flakes

Optional Toppings:

Finely grated parmesan

Breadcrumbs

Lemon wedges

Fill a large pasta pot with about 15 cups of water and season it with the salt. Bring the water to a boil. Add the pasta, and cook it as you normally would, stirring occasionally so it doesn’t stick to the bottom of the pot, until 4 minutes before the pasta should be done (according to the instructions on the package).

When the pasta is just 4 minutes from being al dente, add the broccoli rabe to the pot. Cook both ingredients together until the pasta is just al dente.

Ladle out about a cup of the pasta water and set it aside. Drain the pasta and broccoli rabe into a colander.

Dry out the pot and put it back on the stove. Add the olive oil, garlic, and chile flakes, and cook them just until the garlic is fragrant; the pot should still be pretty hot, so it won’t take very long.

Put the pasta and greens back into the pot with about half of the reserved pasta water, and cook everything, stirring, until the pot is almost dry.

To serve, add the parmesan, breadcrumbs, and/or a squeeze of lemon, if you like.

Photos: courtesy Kate Leahy, Georgia Freedman, courtesy Kate Leahy, Erin Scott (2), Georgia Freedman